A Lanyon Christmas

The year is 1864, and in the recently built dining room of Lanyon Homestead a family is seated around a table decorated with wildflowers, a fruit platter centrepiece and jelly that's struggling to keep its shape in the heat. It's Christmas Day and the temperature is soaring. Yet despite the heat, and the flies and discomfort, the family have gathered to share a meal and celebrate.

This is all conjecture of course, as the records don't give us the minutiae of what occurred when Andrew Cunningham and his wife Jane sat down for Christmas lunch in their newly built home in the shadows of the Tidbinbilla Ranges.

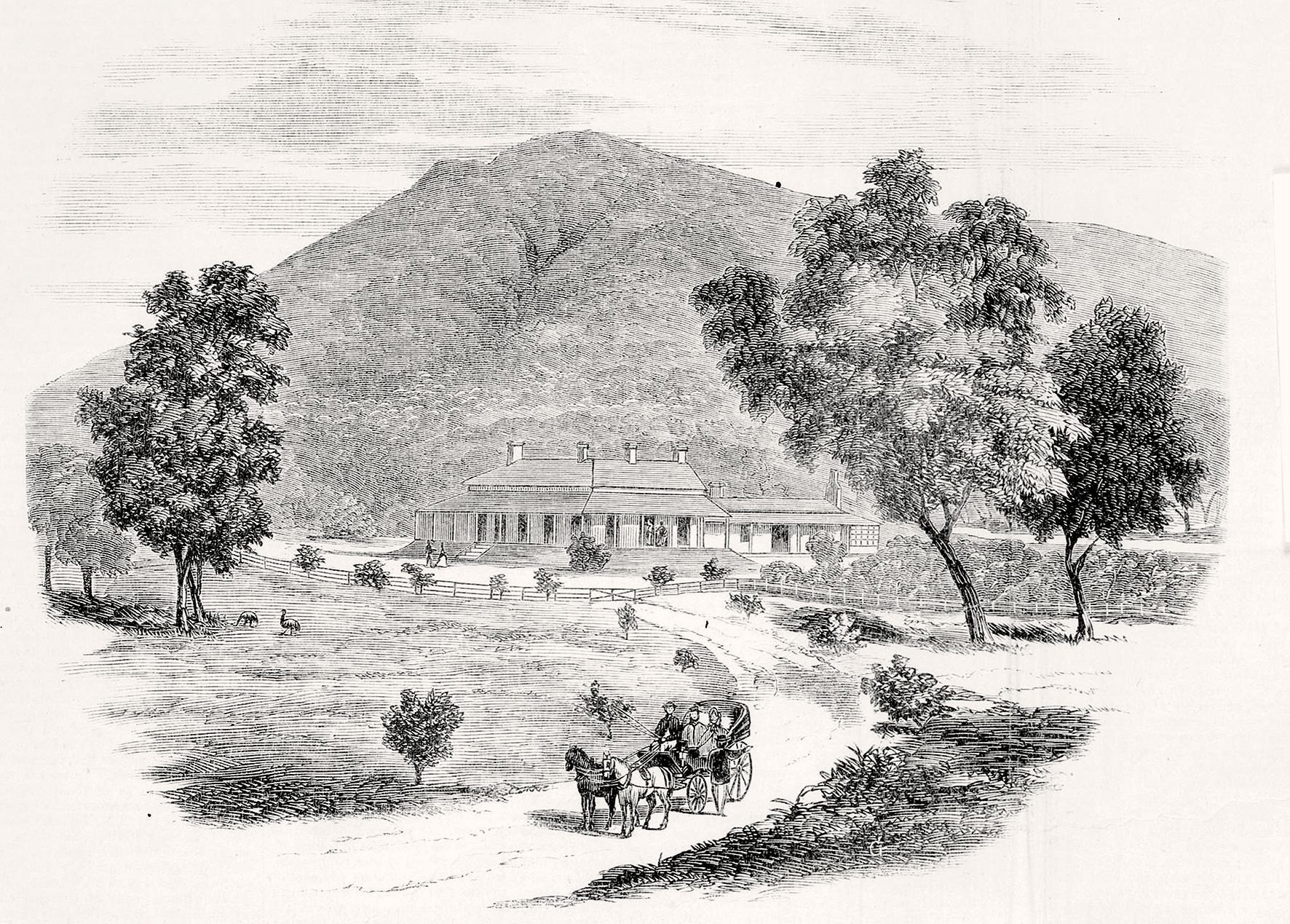

In an engraving of the new "home station" published in the Illustrated Australian News in January 1865, Lanyon is promoted for its bucolic existence. The wide sweeping driveway is already planted with exotics which in generations to come will grow to frame a much grander entrance.

Lanyon Home Station, New South Wales, engraving by Frederick Grosse (1828-1894), published in the Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 25 January 1865, courtesy State Library Victoria

Lanyon Home Station, New South Wales, engraving by Frederick Grosse (1828-1894), published in the Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 25 January 1865, courtesy State Library Victoria

With the homestead a good 170 miles from the colonial centre of Sydney, the Cunninghams' Christmas meal, particularly in the early years, was likely to be food they could source from their own property or locally from the newly established township of Queanbeyan.

And given Andrew Cunningham hailed from Scotland where celebrating Christmas had been frowned upon and even officially banned for many years after the Reformation, it is likely that Hogmanay, celebrations to mark the last day of the year, was a far greater tradition.

A CHRISTMAS LUNCH

From sources available from the time, we can get a picture of what Christmas at Lanyon may have been like for the couple and their brood of children as they settled into life in the antipodes. Perhaps like many others in the new settler classes of the colonies, they were influenced by a new kind of Christmas fervour that was beginning to take hold in Queen Victoria's Britain.

Some clues may be found in the first cookbook to be penned by an Australian, The English and Australian Cookery Book which had the glorious subtitle Cookery for the Many, as well as for the ‘Upper Ten Thousand’. Written by Edward Abbott in 1864 it is an insight into what colonial Australians ate - or aspired to eat - for such an occasion.

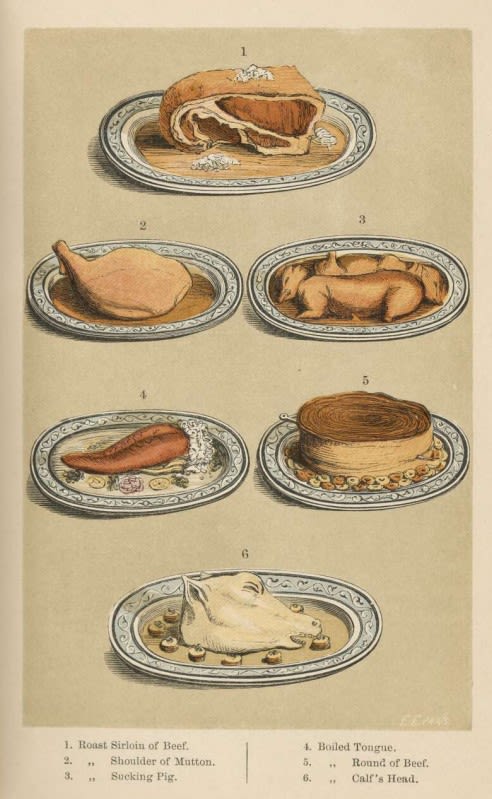

Although Christmas only gets a fleeting mention in the cookbook with recipes for Christmas pudding and Christmas yule cake, some of the dishes that may have been on offer were roast sirloin of beef, roast sucking pig, boiled tongue and calf's head, as well as a tantalising recipe for Christmas Game pie:

“Take a pheasant, a hare, a capon, two pigeons, and two rabbits; bone them and put them into a paste in the shape of a bird, with the livers and hearts, two mutton kidneys, forcemeat and egg balls, seasoning, spice, ketchup, and mushrooms, filled up with gravy made from different bones, and bake sufficiently.”

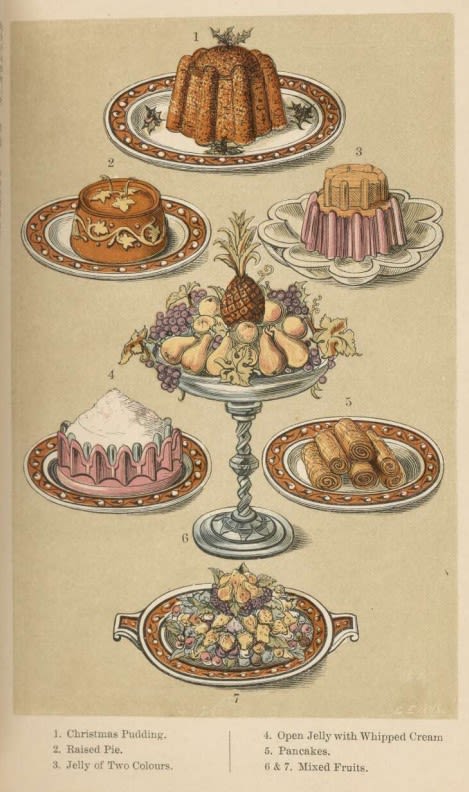

For dessert there was raised pie or jelly of two colours, or open jelly with whipped cream, all set off with a fruit platter with that most exotic of fruits - a pineapple - as the centrepiece.

Abbott dedicated his book to the "ladies of the 'sunny south'" and ever hopeful of a second edition, said he "would feel thankful to receive any additional practical recipes from the ladies of Australia and others".

Perhaps thinking of such practicalities, Abbott included instructions for more local fare - roast emu, kangaroo steamer, roast wombat and "native porcupine".

The English and Australian Cookery Book, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-9574074

The English and Australian Cookery Book, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-9574074

The English and Australian Cookery Book, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-9582057

The English and Australian Cookery Book, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-9582057

It would be fair to say, however, that most "ladies of the sunny south", with their European sensibilities and biases, would have baulked at such a suggestion and would instead have longed for the kinds of delicacies promoted elsewhere.

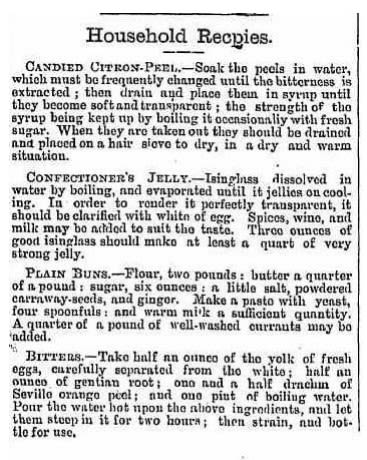

Household Recipes, Australian Town and Country Journal, 7 December 1872, page 20, courtesy of Trove

Household Recipes, Australian Town and Country Journal, 7 December 1872, page 20, courtesy of Trove

Recipes were regularly shared in journals and newspapers for festive foods such as candied citron-peel, jellies, bitters and other specialities while advertisements were appearing in Sydney newspapers as early as the 1830s for Christmas delights such as “fine pudding raisin”, “Jamaica ginger” and “Prime Yorkshire and Westphalia Hams; which, for excellence and flavour, being in high condition, can scarcely be equalled in the colony”.

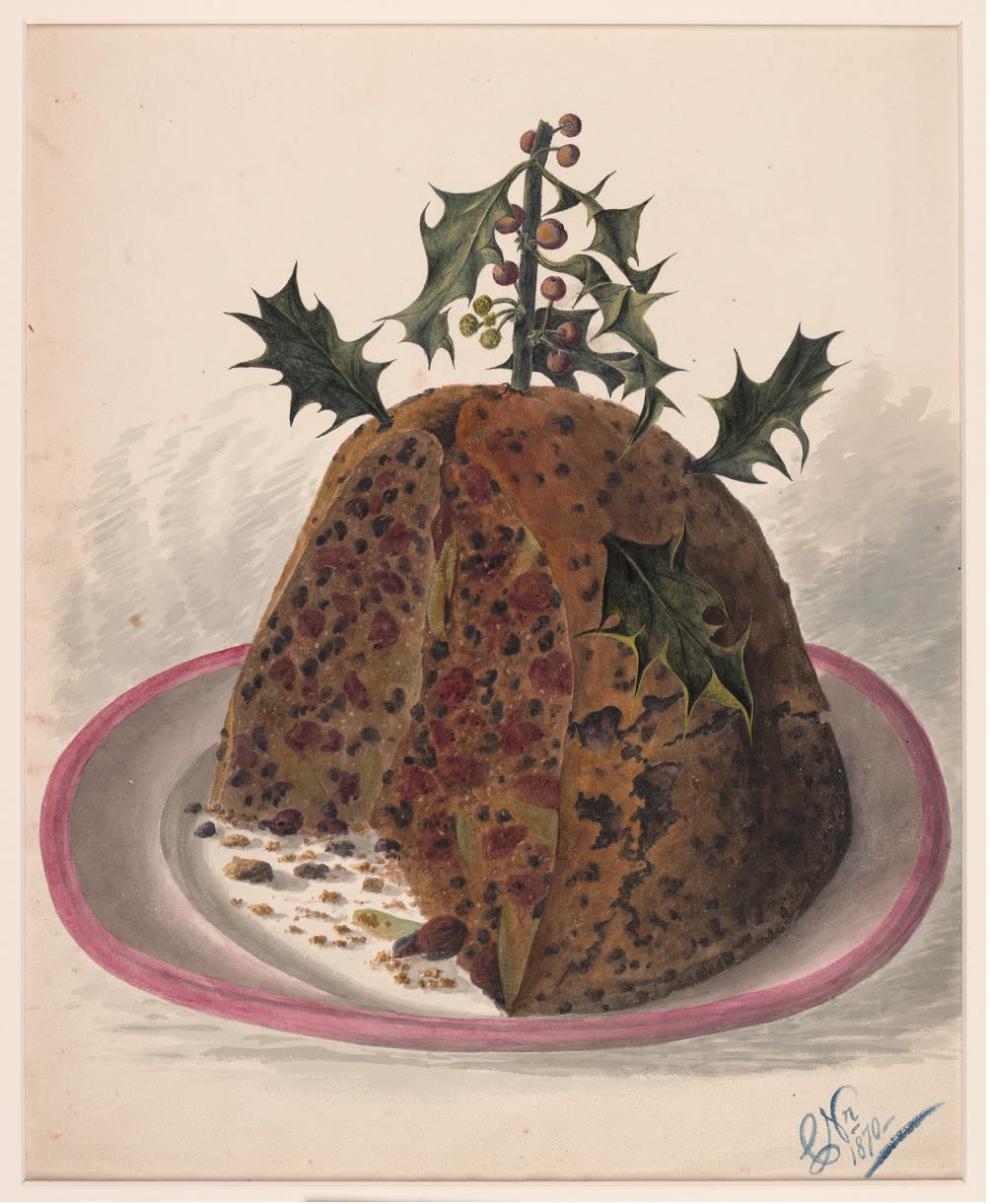

A Christmas pudding, watercolour by Charles Norton (1826-1872), 1870, courtesy State Library Victoria

A Christmas pudding, watercolour by Charles Norton (1826-1872), 1870, courtesy State Library Victoria

In this earlier part of the 19th Century delicacies imported into the colonies would most certainly have been the preserve of the very wealthy or the up and coming. By the time Andrew and Jane Cunningham arrived in Australia in 1844, wealth from agriculture was starting to permeate the colonies, and with the discovery of gold in the 1850s the monied classes would grow exponentially.

Whether the Cunninghams, who reportedly did well due to Andrew's business acumen, had the means in their early years at Lanyon to send away for such luxuries remains something of a mystery.

Christmas 1878 - The Hamper, engraving published in Illustrated Sydney News, 21 December 1878, courtesy State Library Victoria

Christmas 1878 - The Hamper, engraving published in Illustrated Sydney News, 21 December 1878, courtesy State Library Victoria

By the second half of the 19th Century, however, it is highly probable that Jane Cunningham in particular was devouring the illustrated journals that became one of the greatest influences on the way colonial Australians absorbed Christmas traditions.

As Colin Bannerman writes in The Upside-Down Pudding- A Small Book of Christmas Feasts many of the new readers for these journals were to be found in country areas.

“Time moved more slowly for them, and many were content to have their news in a weekly budget, with less high-minded editorialising than city readers might expect. And they wanted it with plenty of light reading- short stories and poems- and useful information on a wide range of practical subjects like how to keep a kitchen garden, how to brew beer or make bread at home, and what to wear in order not to look ‘up-country’”.

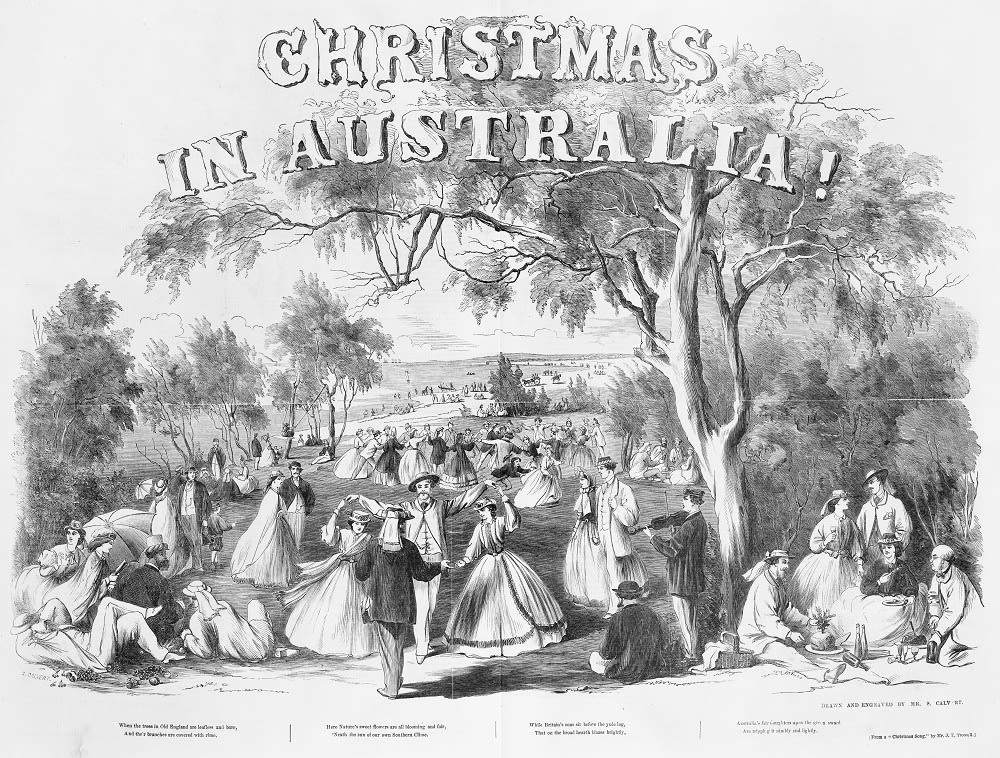

Christmas in Australia!, drawn and engraved by Samuel Calvert, published in The Illustrated Melbourne Post, 24 December 1863, courtesy State Library Victoria

Christmas in Australia!, drawn and engraved by Samuel Calvert, published in The Illustrated Melbourne Post, 24 December 1863, courtesy State Library Victoria

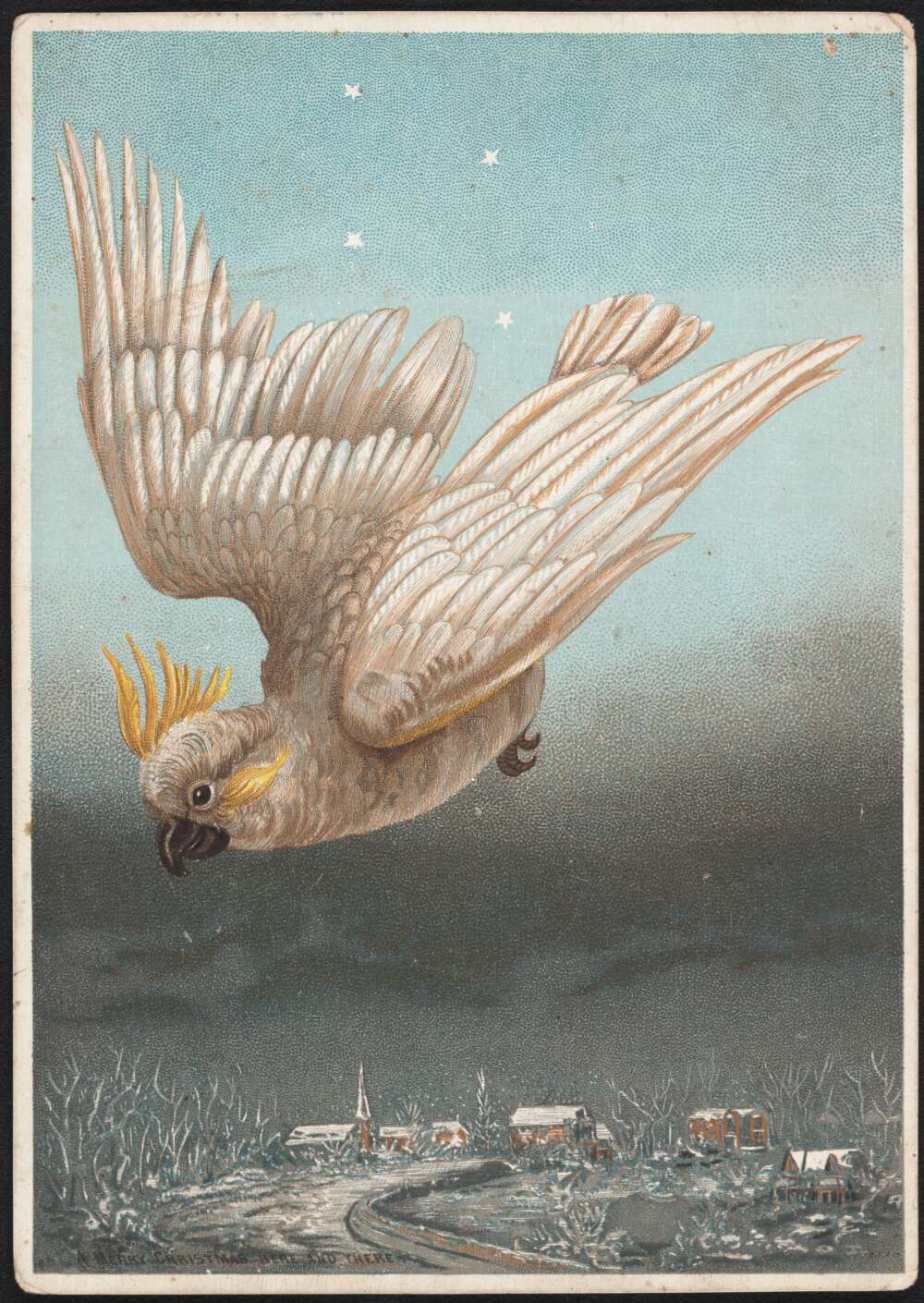

A Merry Christmas Here and There, Christmas card, Gibbs, Shallard & Co, 1885, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-153042607

A Merry Christmas Here and There, Christmas card, Gibbs, Shallard & Co, 1885, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-153042607

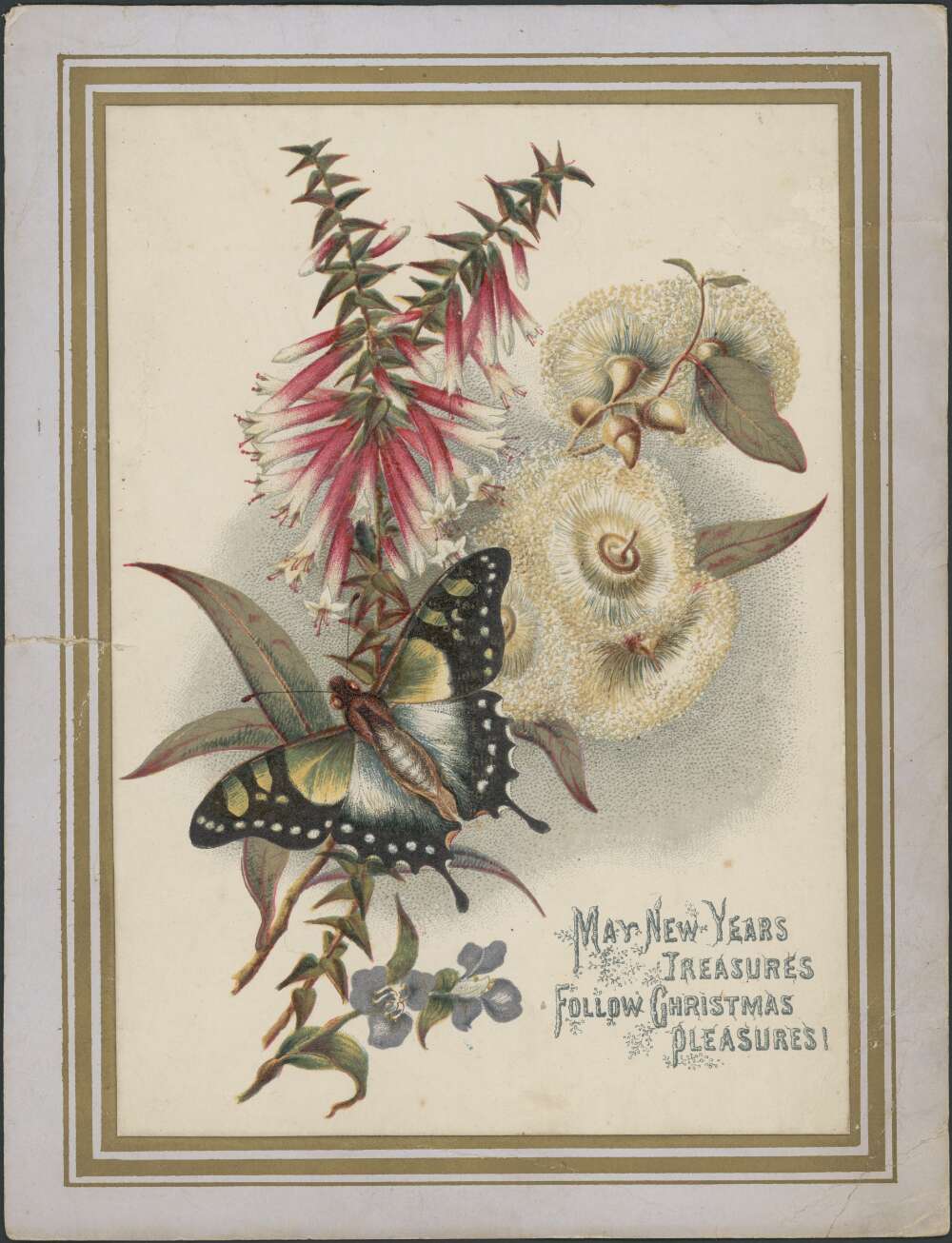

Christmas card designed by Helena Forde (1832-1910), John Sands, circa 1881, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-137340979

Christmas card designed by Helena Forde (1832-1910), John Sands, circa 1881, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-137340979

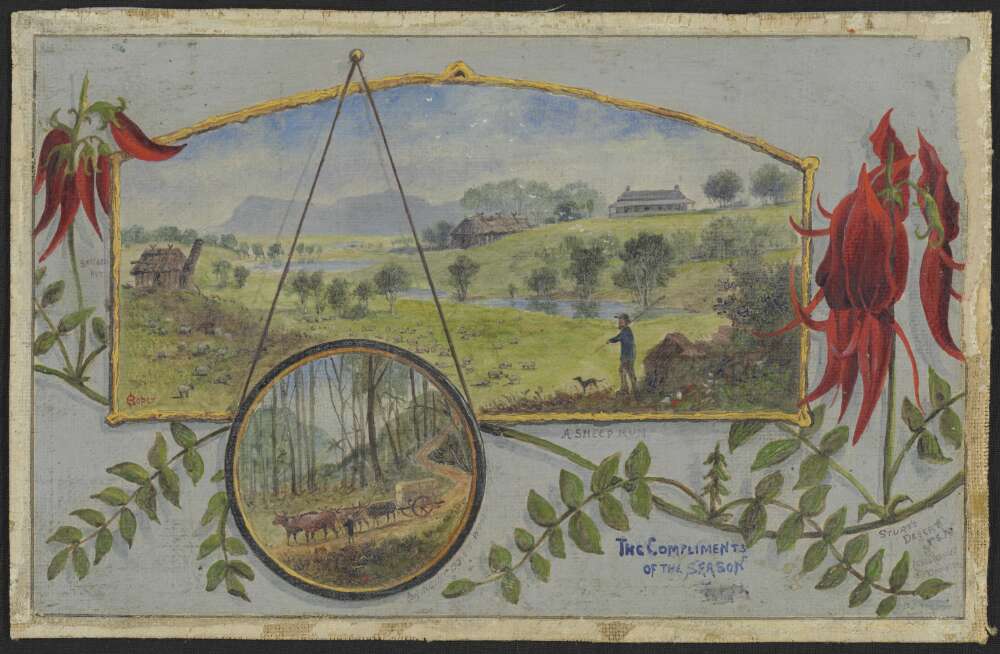

Christmas card featuring A sheep run: bringing down wool, a painting by Edward Roper (circa 1830-1904), circa 1855, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-134313305

Christmas card featuring A sheep run: bringing down wool, a painting by Edward Roper (circa 1830-1904), circa 1855, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-134313305

AN AUSTRALIAN CHRISTMAS

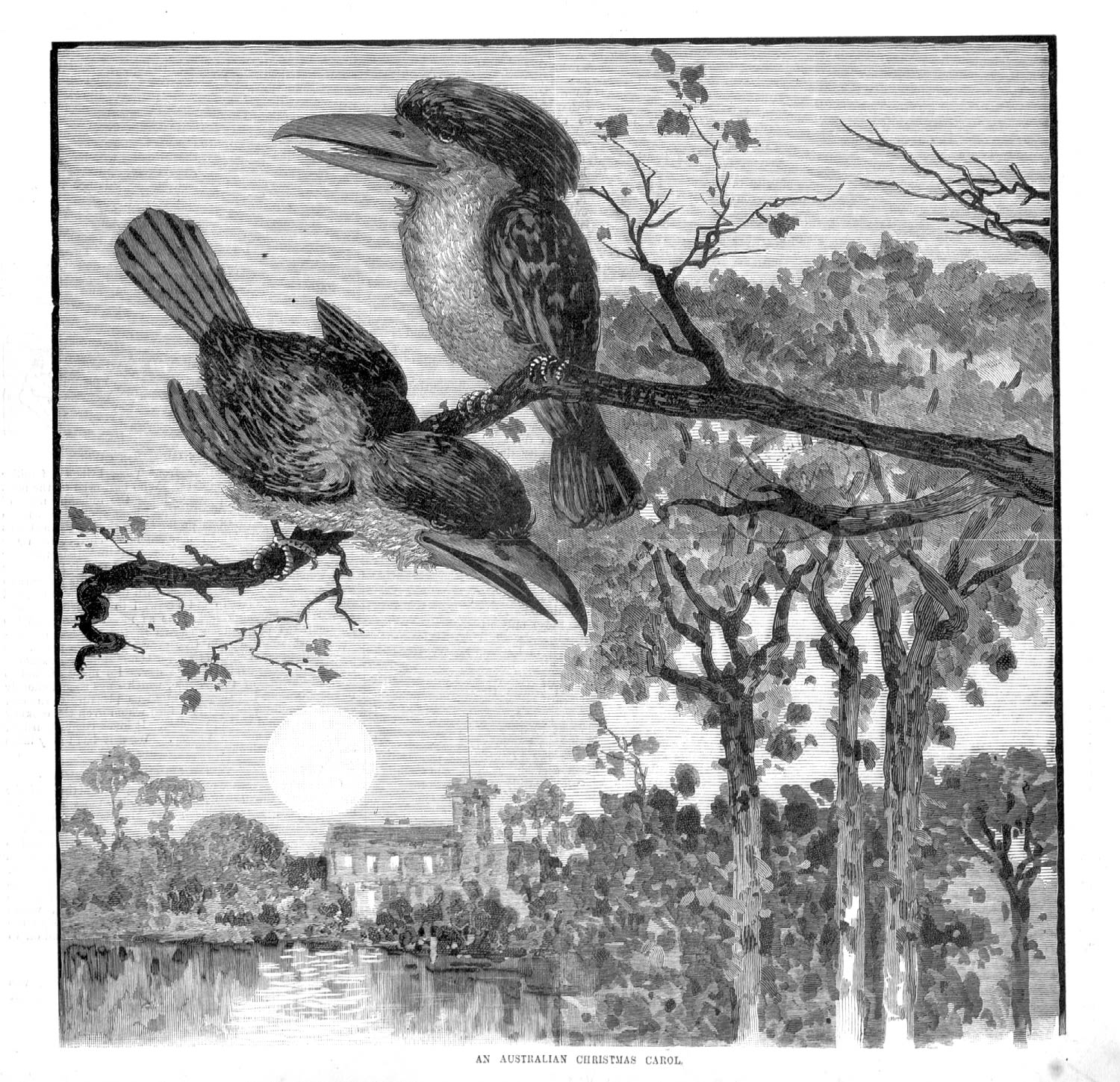

Along with the increasing popularity of Christmas cards that celebrated Australian flora and fauna, scenes and motifs, what these illustrated journals were very good at promoting was a particular brand of Australian Christmas.

Titles such as The Town and Country Journal, The Australasian Sketcher and the Illustrated Sydney News celebrated the notion of outdoor picnics in the bush or in lush fern gullies, cricket matches between friends or a day of swimming as being quintessential elements of Christmas in the colonies.

Photograph of colour illustration by Nicholas Chevalier (1828-1902) featured in Illustrated Australian News, 23 December 1865, courtesy State Library Victoria

Photograph of colour illustration by Nicholas Chevalier (1828-1902) featured in Illustrated Australian News, 23 December 1865, courtesy State Library Victoria

A columnist for Melbourne's The Argus JF Hogan noted in his compendium of works An Australian Christmas Collection in 1886, the difference between those born in Australia “in a sunny land” and their parents where “their recollections of the great social event of the year are associated with bleak winds and wintry storms”:

“Your native Australian cannot understand or appreciate such a Christmas. The only Christmas with which he is acquainted is one celebrated with all the joyous excitement of external freedom; an annual event signalised by delightful reunions in the parks and gardens, healthful excursions into the country, or boating expeditions down the river.”

While we don’t know how the Cunninghams observed Christmas Day in their early years at Lanyon, there is a ring of truth to the sentiment. In a photograph taken decades later during Christmas 1914 and saved in the family album of Mary Dunlop, Andrew and Jane’s granddaughter, a row of children are pictured on their horses - the bright sunlight casting long shadows on the pasture.

It is a scene that celebrates a life outdoors and is a far cry from the snowy landscapes of a British Christmas.

The Cunningham family, Christmas 1914, from the family photograph albums of Mrs WAS Dunlop (Mary Paule Cunningham of Lanyon), courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-147812373

The Cunningham family, Christmas 1914, from the family photograph albums of Mrs WAS Dunlop (Mary Paule Cunningham of Lanyon), courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-147812373

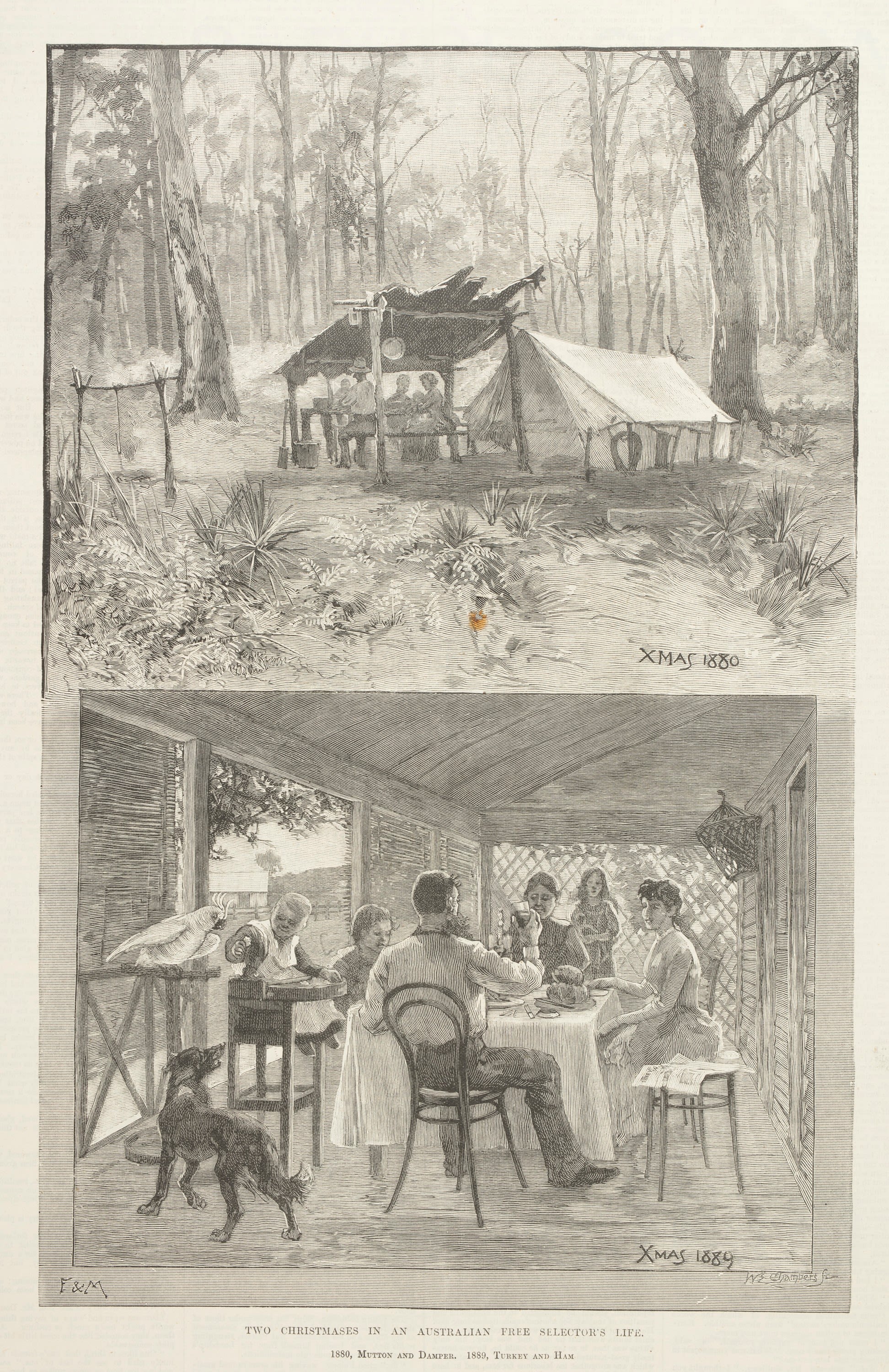

As Bannerman observes, there was a particular nationalistic fervour in the late 1800s where the depictions of Christmas not only marked the passing of time but also colonial achievements.

One illustration in the Sydney Mail Christmas Supplement in 1889 titled “Two Christmases in an Australian Free Selector’s Life” showed two Christmas scenes: an 1880 Christmas where mutton and damper were served in an open air hut, and an 1889 Christmas of turkey and ham in a far more comfortable home.

Two Christmases in an Australian Free Selector's Life, The Sydney Mail Christmas Supplement, 21 December 1889, page 17, courtesy State Library of NSW

Two Christmases in an Australian Free Selector's Life, The Sydney Mail Christmas Supplement, 21 December 1889, page 17, courtesy State Library of NSW

This settler, not unlike the Cunninghams of Lanyon, had in the views of the colonial classes, made a good life for themselves despite the challenges.

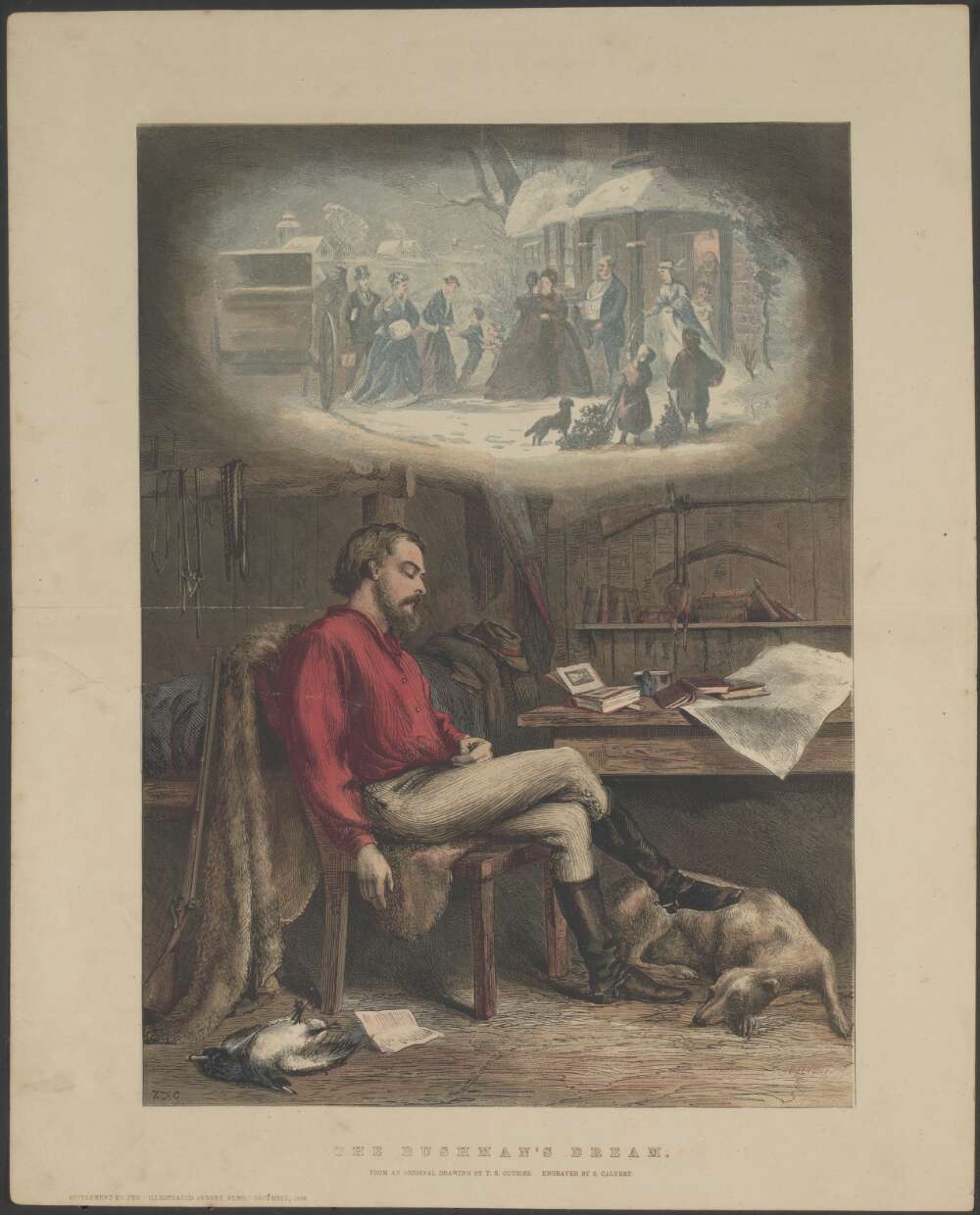

Alongside this nationalistic narrative, what the illustrations also acknowledge is a yearning for the white Christmases of "back home". A common trope in the early journals was contrasting the picturesque snow covered scenes in Britain with the harsh climate and conditions of the colonies.

A classic example, "The Bushman's Dream", was an engraving by Samuel Calvert of an original drawing by TS Cousins which was published in December 1869 in the Illustrated Sydney News. It depicts a bushman, exhausted from a day's work with his dog at his feet, dreaming of snow capped roofs and the warmth of friends and family far away.

The Bushman's Dream, 1869, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-135891983

The Bushman's Dream, 1869, courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-135891983

CHRISTMAS TRADITIONS

What is particularly fascinating about this nostalgia for a picture-perfect white Christmas, is that this very English notion of Christmas celebrations was a recent phenomenon even in the home country.

Any yearning colonial Australians felt, was a longing for somewhat concocted traditions.

As Judith Flanders writes in Consuming Passions-Leisure and Pleasure in Victorian Britain, it was not until the mid-1830s that Christmas with all the trimmings started to take hold in the popular imagination in Britain:

“When it did, it was rather like those mythic sports of the rural past. The holiday was presented as a re-creation of what in fact had never existed: an idealized, prettified past was summoned up for nostalgic appreciation.”

Flanders explains that the Christmas we think of today was constructed for the most part during Victorian-era England. Previously it was the Twelfth Night, the Feast of Epiphany on January 6, that had been more commonly celebrated as a family feast, when a bean and a pea were baked into the Twelfth Night cake to be found by a lucky two who were crowned the King and Queen of the night.

It was a practice not unlike the hidden sixpence in Christmas puddings that would supersede it.

The Christmas Pudding - "I can stir it", illustration in Australian Town and Country Journal, 17 December 1887, pg 29, courtesy National Library of Australia

The Christmas Pudding - "I can stir it", illustration in Australian Town and Country Journal, 17 December 1887, pg 29, courtesy National Library of Australia

Even in Abbott's English and Australian Cookery Book the first cake recipe in his list is for a Twelfth Cake. While there is a detailed recipe for Christmas pudding in Abbott's book, it was a relatively recent dessert. The pudding's origin was a rather unappetising sounding plum broth, or plum porridge, which was eaten as a soup during Christmas at St James during the reign of George III in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

With ingredients of veal, beef, sugar, lemon, oranges, hock, sherry, currants and prunes as well as a smattering of spices such as nutmeg, cinnamon and cloves it was topped off by a touch of cochineal - no doubt an attempt to hide what was most likely a fairly sludgy colour.

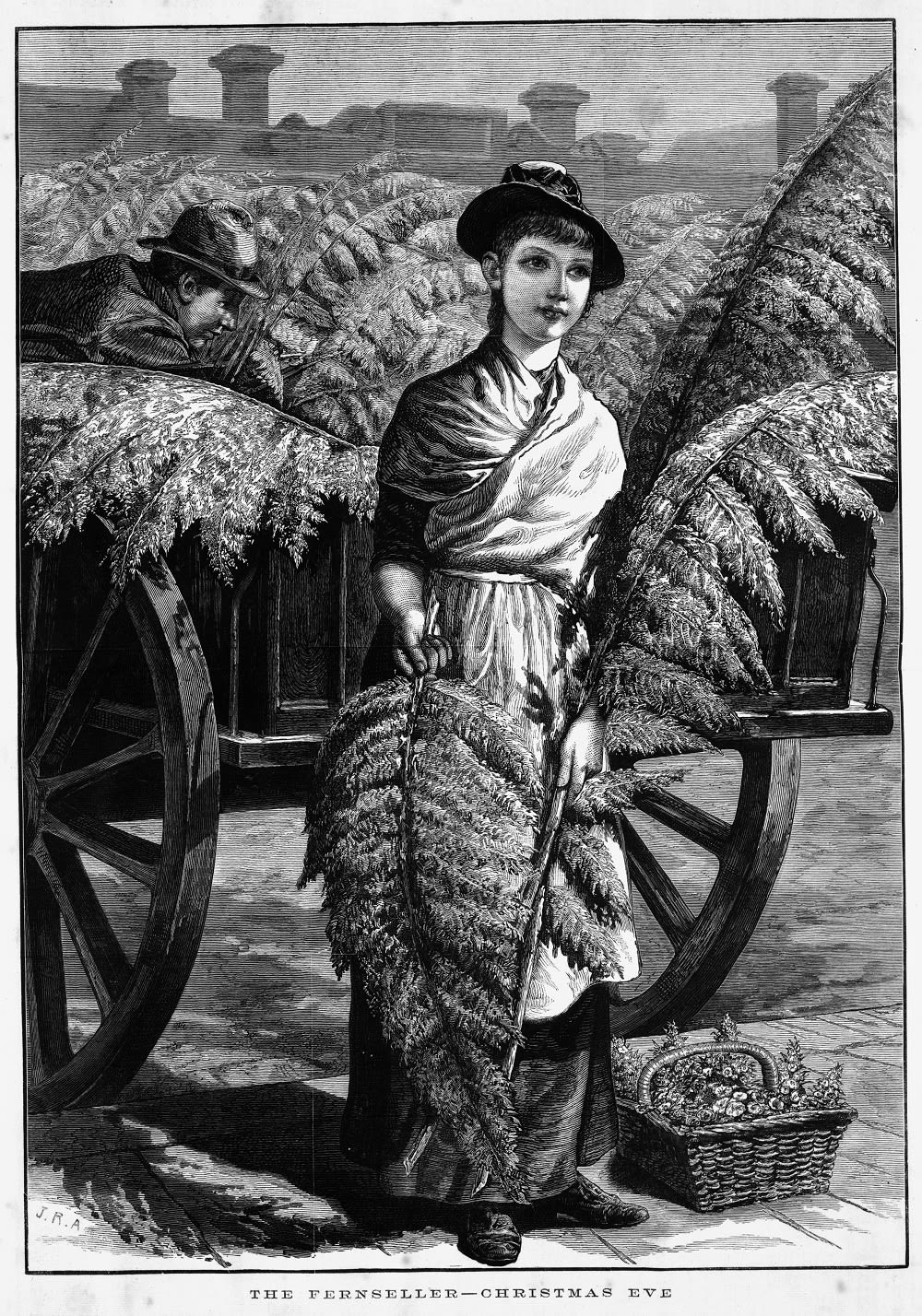

The Fernseller - Christmas Eve, engraving by Julian Rossi Ashton (1851-1942), published in the Illustrated Australian News, 24 December 1879, courtesy State Library Victoria

The Fernseller - Christmas Eve, engraving by Julian Rossi Ashton (1851-1942), published in the Illustrated Australian News, 24 December 1879, courtesy State Library Victoria

A DECORATED CHRISTMAS

There were other changes to Christmas as well. In 1840 just a few years before Andrew and Jane Cunningham arrived in Australia, Albert, Queen Victoria’s beloved husband, put up a Christmas tree in the German tradition at Windsor Castle.

Although there are some records of Christmas trees popping up in England before Victoria and Albert decorated their tree, an illustration of the royal family sitting around their beautifully decorated tree was published in 1848 and became a marketer’s dream. Soon dedicated Christmas trees would become a popular addition for fashionable families in Britain and elsewhere in the Empire.

The Christmas tree - some of its fruits, Australian Town and Country Journal, 27 December 1890, pg 19, courtesy State Library of NSW

The Christmas tree - some of its fruits, Australian Town and Country Journal, 27 December 1890, pg 19, courtesy State Library of NSW

As for the Cunninghams who arrived in Australia at the cusp of this newfound fascination with Christmas adornments, it is probable that in their early years they stuck to the well-worn tradition of gathering greenery to deck their homestead in celebration rather than a stand alone tree.

In England before the proliferation of the Christmas tree, festive decorations such as holly and ivy were gathered in rural areas and a central decoration was a "kissing bough" adorned with mistletoe.

Flanders points out this was a country custom "often considered suitable only for rustics and servants in the early part of the nineteenth century" however magazines such as Punch introduced it to the middle-classes in the 1840s and 50s with cartoons that celebrated "mistletoe capers".

In Australia some writers yearned for flora more local. A poem published in the Australian Town and Country Journal in December 1888 was titled "Under the Wattle" and asked wistfully "Why should not wattle do for mistletoe?... Since it is here, and you, I hardly know Why wattle should not do."

A poem published in Australian Town and Country Journal, 22 December 1888, page 12, courtesy Trove

A poem published in Australian Town and Country Journal, 22 December 1888, page 12, courtesy Trove

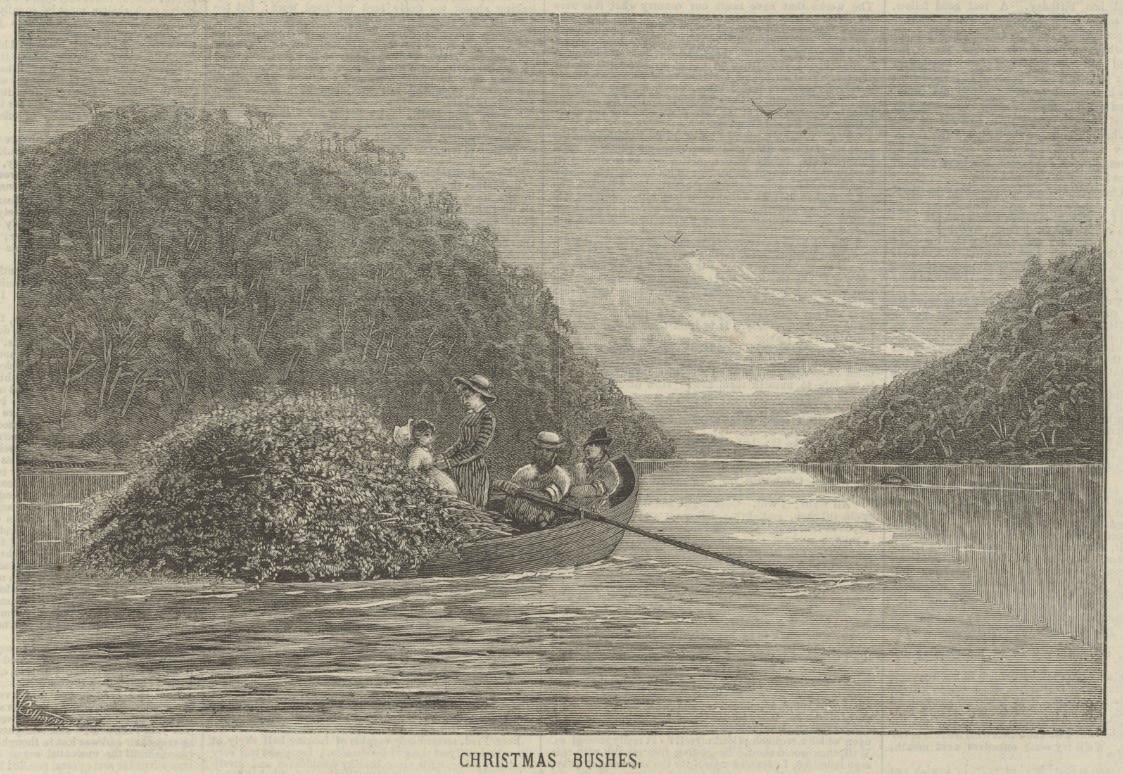

Christmas trees do make an appearance in the Australian illustrated journals of the late 1800s, but readers were equally likely to see illustrations which depicted the gathering of greenery with a particular Australian flavour.

Ferns were a particular favourite as were native wildflowers, but the one species that would really capture the imagination of colonials in New South Wales was the Ceratopetalum gummiferum - commonly known as the Christmas bush that bursts into colour in summer, its sepals turning from green to red as if on cue around Christmas time.

Christmas Bushes, illustration in The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 23 December 1882, pg 1125, courtesy National Library of Australia

Christmas Bushes, illustration in The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 23 December 1882, pg 1125, courtesy National Library of Australia

Did Andrew and Jane Cunningham source their decorations from these merry bands of collectors in coastal regions and gullies who were so enthusiastic for their love of the Christmas bush that at one stage it became increasingly difficult to find?

Did they find their foliage more locally, or join the latest fashions spurred on by Queen Victoria and her beloved Albert and decorate their own Christmas tree? What did they have on their Christmas table - or at their picnic outdoors - and how did it change over time?

Andrew Cunningham died in 1887 and his wife Jane in 1895. After Andrew's death, it was their son Andrew Jackson Cunningham who, after a stint abroad, lived at Lanyon in a somewhat bachelor existence before he married 24-year-old Louisa Leeman in 1905.

AJ Cunningham was so intent on making his young bride, who was 34 years his junior, comfortable that he built a new wing at Lanyon with a private bedroom for Louisa resplendent with the latest fashions.

On Christmas Day 1910 a moment in time was captured - AJ, resplendent in white, stands behind his young wife Louisa, enjoying tea with relatives and the household help.

In the eyes of the settler classes, the homestead in the shadows of the Tidbinbilla Ranges had truly arrived.

Christmas, Lanyon Homestead, 1910. Standing left to right: Jane Blewitt (parlour maid), AJ Cunningham, Willy Cunningham (nephew of AJ), Margaret Grady (housemaid). Sitting left to right: Misses McCarthy (two nieces of AJ), Mrs Leman (mother of Louisa), Louisa Cunningham, Bessie Leman (sister to Louisa), Miss Purkiss (housekeeper), ACT Historic Places collection

Christmas, Lanyon Homestead, 1910. Standing left to right: Jane Blewitt (parlour maid), AJ Cunningham, Willy Cunningham (nephew of AJ), Margaret Grady (housemaid). Sitting left to right: Misses McCarthy (two nieces of AJ), Mrs Leman (mother of Louisa), Louisa Cunningham, Bessie Leman (sister to Louisa), Miss Purkiss (housekeeper), ACT Historic Places collection

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the Canberra Region.

The region has always been an important meeting place and significant to other Aboriginal groups who have celebrated culture through the arts and cultural practices for tens of thousands of years.

Writer and digital producer: Cathy Pryor, Curator of Exhibitions and Research, ACT Historic Places

Archival images: National Library of Australia, State Library Victoria, State Library of NSW

Background photographs: Annie Spratt on Unsplash

References:

Abbott E, 1864, The English and Australian Cookery Book: cookery for the many as well as for the 'upper ten thousand', Sampson Low, Son and Marston, London

Bode K (editor) and Whelehan I (introduction), 2018, Christmas Eve in a Gum Tree and Other Lost Australian Christmas Stories, Obiter Publishing, Canberra

Bannerman C, 1999, The Upside-Down Pudding- A Small Book of Christmas Feasts, NLA, Canberra

Flanders J, 2006, Consuming Passions-Leisure and Pleasure in Victorian England, Harper Press, London

Hogan JF, 1886, An Australian Christmas Collection, Alex McKinley and Co, Melbourne

Stapleton M and McDonald P, 1981, Christmas in the Colonies, David Ell Press, Sydney

An Australian Christmas Carol, wood engraving by Alfred Martin Ebsworth, published in the Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, 13 January 1886, courtesy State Library Victoria

An Australian Christmas Carol, wood engraving by Alfred Martin Ebsworth, published in the Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, 13 January 1886, courtesy State Library Victoria