Nearly 200 years ago, James Ainslie ventured to the Limestone Plains with 700 sheep. Here, he settled and established a sheep station on behalf of his employer, Robert Campbell. The philanthropic Campbell family grew their estate, added more than 40,000 sheep to their station, funded estate workers to emigrate, built a dairy, church, school and workers cottages, provided sport and social activities, and extended their house. This estate became known as Duntroon.

The exhibition at Canberra Museum and Gallery brings together objects and images from the Duntroon estate and the families that lived and worked in this then-remote outpost.

The Campbell Family

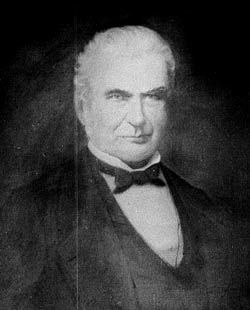

Robert Campbell was born on 28 April 1769 at Greenock, Scotland. After spending his early life in Scotland, he and his brother John ventured to Calcutta, India in the 1790s.

Oil painting of Robert 'Merchant' Campbell by unknown artist based on a charcoal drawing by Charles Rodius. Courtesy of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

Oil painting of Robert 'Merchant' Campbell by unknown artist based on a charcoal drawing by Charles Rodius. Courtesy of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

By 1796, the Campbell brothers were breaking new ground by supplying goods to the newly-established colony. After the wrecking of their merchant vessel 'Sydney Cove', Robert travelled to Sydney to resolve the business associated with the loss of the ship.

After seeing the new colony for himself, Robert decided that there was an opportunity to make a name for himself and his family, and was determined to stay. His business thrived and led to him being coined, 'Merchant Campbell'.

In 1806, one of Robert's merchant vessels, the 'Sydney', was requisitioned by the British Government to supply the colony with rice due to food shortages for the growing population. During a storm, the vessel was lost. Nearly 20 years later, Robert received land and sheep as compensation for the loss.

First overseer of Duntroon estate

Former soldier and self-proclaimed Battle of Waterloo veteran James Ainslie was given the job of selecting the perfect spot to establish a new station for Campbell in 1825. From Bathurst, he ventured southwards with a 700-strong flock of sheep. He was guided towards the Limestone Plains by a local unnamed Aboriginal woman. Upon reaching the area, with her help, he settled on the Pialligo/Duntroon area as the prime site for Campbell's sheep station.

After a decade of managing the station, Ainslie was given his orders to leave due to 'irregularities and insubordination'. During his tenure, he had increased the original flock to over 20,000 head of sheep.

Charles Campbell steps up

Robert married Sophia Palmer and together they had 7 children; John, Robert, Sophia, Charles , Sarah, George, and Frederick. Robert was an absentee landlord so in 1835, at the age of 25, Charles Campbell (Robert's third son) took up the role of manager of the estate.

Charles Campbell MLC. c. 1885. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales

Charles Campbell MLC. c. 1885. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales

Charles was a progressive manager - he funded the passage of shepherds from Scotland, built cottages for the workers, provided each family with 2 acres of land to grow their own vegetables and to keep a cow, and oversaw the founding and building of St. John's Church and School on behalf of his father.

When Robert Campbell died in 1846 (in the garden at Duntroon), Charles continued to run the estate before sailing to England in 1854 to study law. A few years later, the estate became the home of George Campbell - Charles's younger brother - his wife Marrianne, and their two eldest children.

George 'The 'Squire of Duntroon' Campbell and his family

George Palmer Campbell (1818-1881) was the fourth son of Robert Campbell. He moved to Duntroon in 1857 from Sydney with his wife, Marrianne, and his eldest children, John and Sophia.

George was a respected employer, nicknamed 'the squire of Duntroon', who created a village-feel to his estate. He was also a keen cricketer and horseman. Stanley Howard, a future clergyman visiting the area, after meeting George for the first time, recorded his thoughts on the squire:

Mr Campbell is rather a nice looking, elderly gentleman; there is nothing of the rough style about him. He is very wealthy... He takes a great interest in church matters; and is spending a large amount on the improvement of this Church [St John's]. Diary of Stanley Howard, November 1872

As a wealthy landowner, George would have corresponded and conducted business with people within the colony and further afield. The Campbell family embossing stamp shows how important documents would have been marked with the family crest.

Campbell family embossing stamp, 19th century. On loan from the Australian Army Museum Duntroon.

Campbell family embossing stamp, 19th century. On loan from the Australian Army Museum Duntroon.

George and Marrianne were well-liked in their community; in 1876, their employees and local children presented them with silverware before they embarked on a visit to England. After suffering ill health, George died five years later in Bournemouth, England having never had the chance to return to his beloved Duntroon. He was 63 years old.

Marrianne Collinson Campbell (nee Close) (1827-1903) was born into a prominent settler family based in the Hunter Valley.

From an early age, she enjoyed nature and recorded many Australian wildflowers – her artistic and observational skills being nurtured by her father and great-aunt. During her early teenage years, Marrianne trained under Conrad Martens in Sydney. It was here that she honed her intricate, meticulous painting style. Marrianne came to be an accomplished watercolourist. An article in The Queanbeyan Age describes a bazaar held at Duntroon in October 1874, where works by Marrianne were on display, including ‘some very fine water-colour paintings of Australian wild-flowers, including the well-known fringed-violet and the bignonia of Queensland, by Mrs Geo. Campbell.’

Oxylobium procumbens and Correa reflexa, 1873 by Marrianne Campbell. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Oxylobium procumbens and Correa reflexa, 1873 by Marrianne Campbell. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Upon the death of her husband, George, in England, she returned to Duntroon and lived out her life as 'chatelaine'. Her obituary states,

She taught, as was her wont, the sabbath-school she had organised and successfully maintained for many years for the benefit of the children of her servants and tenentary. The Queanbeyan Observer, 5 May 1903

Sophia Susanna Campbell (1857-1885) was the eldest daughter of George and Marrianne, born in 1857 in Sydney before the family relocated to Duntroon.

Petticoat worn by Sophia and/or Sarah Campbell, c. 1860s. CMAG Collection; Gift of Pat and Emma Campbell, 2017

Petticoat worn by Sophia and/or Sarah Campbell, c. 1860s. CMAG Collection; Gift of Pat and Emma Campbell, 2017

According to Stanley Howard, Sophia (or Sophy as she was often called) was 'the far-famed young ‘belle’ of whom I have so often been "warned" when telling people that I was going to stay here.'

Beautiful and accomplished, Sophia dressed in the latest fashions; a top hat with a sash of material finishes her outfit in this photograph.

Sophia died at Duntroon on 30 May 1885. The local press reported that her death was the result of a fall. However, some have speculated that the fall might not have been an accident... this may forever remain a mystery. She was 27 years old at the time of her death.

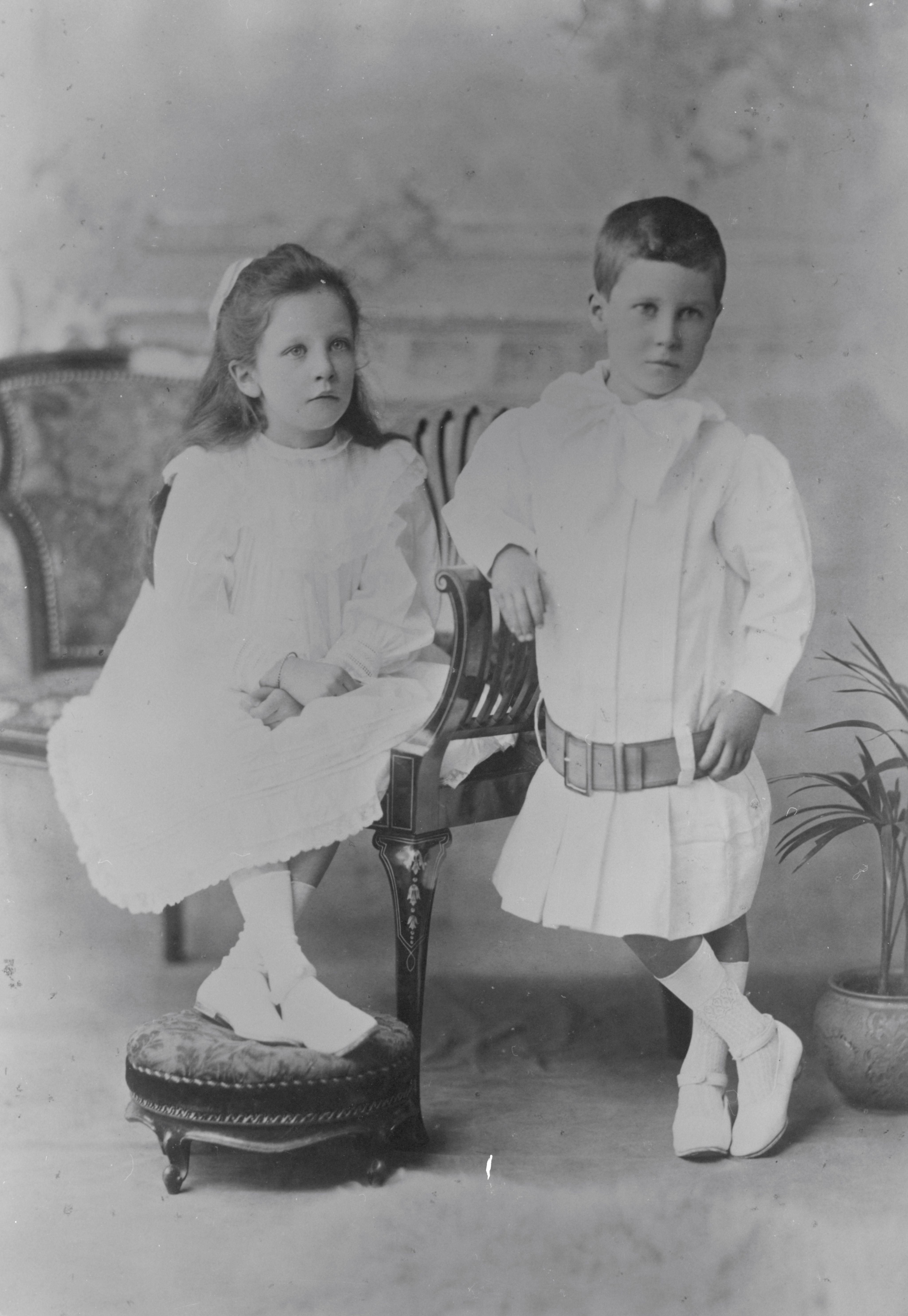

Frederick Arthur (Fred) Campbell (1861-1931) was the second son of George and Marrianne.

Other family photographs show Frederick enjoying goat-led buggy rides and posing with a hunting rifle. The Campbell family enjoyed hunting possums and 'bears' (koala) and made their own blankets from the furs.

Campbell family children enjoying a ride in a buggy drawn by four goats, c. 1870s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Campbell family children enjoying a ride in a buggy drawn by four goats, c. 1870s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Frederick went on to own Woden Station, before it passed to his son, Arthur. Frederick died in Rose Bay, Sydney, at the age of 70.

Edward (Eddie) Charles Close Campbell (1862-1905) was the last of the Campbell family dynasty to live at Duntroon. He married Ethel Blomfield and together they had 5 children.

'Eddie' Campbell, c. early 1890s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

'Eddie' Campbell, c. early 1890s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Ethel Amy Blomfield, c. early 1890s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Ethel Amy Blomfield, c. early 1890s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Eddie's elder brother, John Campbell leased and then sold Duntroon estate to the Australian Government in 1913 to establish the Royal Military College.

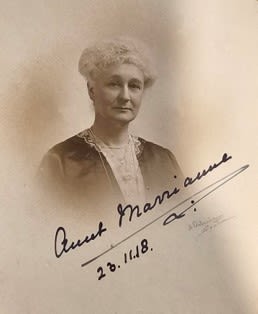

Sarah Marrianne Emily Campbell (1866-1942). Sarah, who went by the name Marrianne, married Cecil Treherne in 1891 and moved to England. She kept in contact with her family members in Australia sending letters with accompanying portrait photographs. She also visited Duntroon, with her family, prior to the death of her mother.

Sarah Marrianne Emily Treherne (nee Campbell), 1918. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Sarah Marrianne Emily Treherne (nee Campbell), 1918. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Sarah died in Southsea, England, in January 1942. She was 76 years of age.

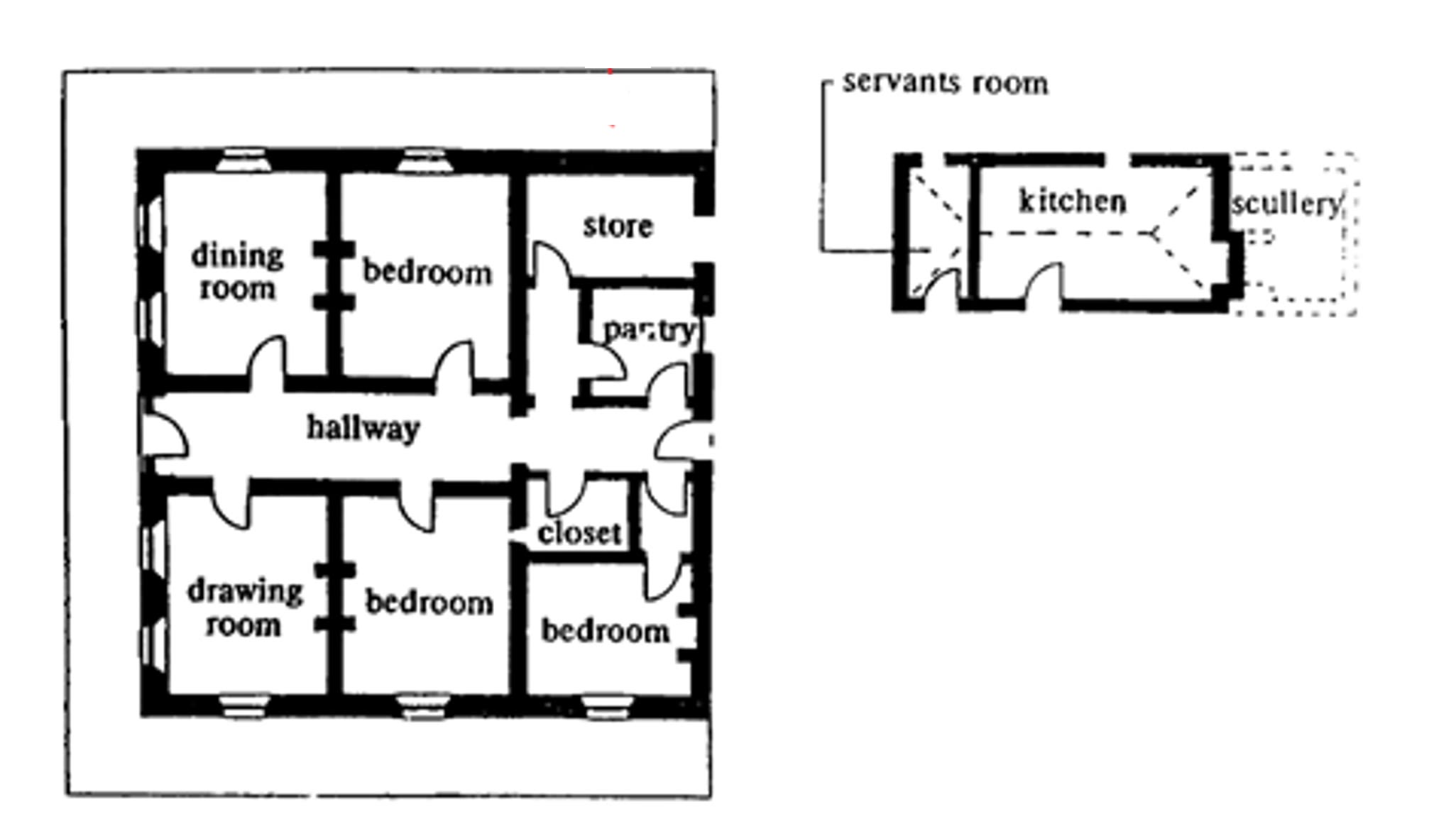

The House

Limestone Cottage, as it was originally known, was built between 1832-35. The external sandstone was quarried from nearby Mount Ainslie. It was a single storey home with three bedrooms, a drawing room, dining room and grand hallway. The kitchen was in a separate building, a typical design of the time, to help avoid fires (and smells) spreading into the main living quarters.

Plan of Limestone Cottage c. 1833. Courtesy of Tour Guide Booklet RMC Duntroon, 1996

Plan of Limestone Cottage c. 1833. Courtesy of Tour Guide Booklet RMC Duntroon, 1996

This sketch was made by Sophia Ives Campbell, sister of Charles Campbell who was the manager of Duntroon estate, in 1841. It shows the Limestone Cottage with separate kitchen wing, and the estate gates (to the left in the sketch).

Duntroon, N.S. Wales. December 1841. Pencil sketch by Sophia Ives Campbell, daughter of founder Robert Campbell. Courtesy of the Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales

Duntroon, N.S. Wales. December 1841. Pencil sketch by Sophia Ives Campbell, daughter of founder Robert Campbell. Courtesy of the Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales

The cottage had grand French windows and high ceilings, as well as an oversized front door. It was a substantial stone structure with thick walls that kept the home cool during the hot summer months and warm during the winter months. It had a wood shingle roof, held in place with handmade nails like those below.

Wooden shingle and handmade nails from the Duntroon house site, c. 1800s. On loan from the Australian Army Museum Duntroon.

Wooden shingle and handmade nails from the Duntroon house site, c. 1800s. On loan from the Australian Army Museum Duntroon.

Growing wealth, growing family, extended home

George and Marrianne Campbell arrived at Duntroon in 1857. Shortly after, plans were afoot to add a substantial two-storey extension.

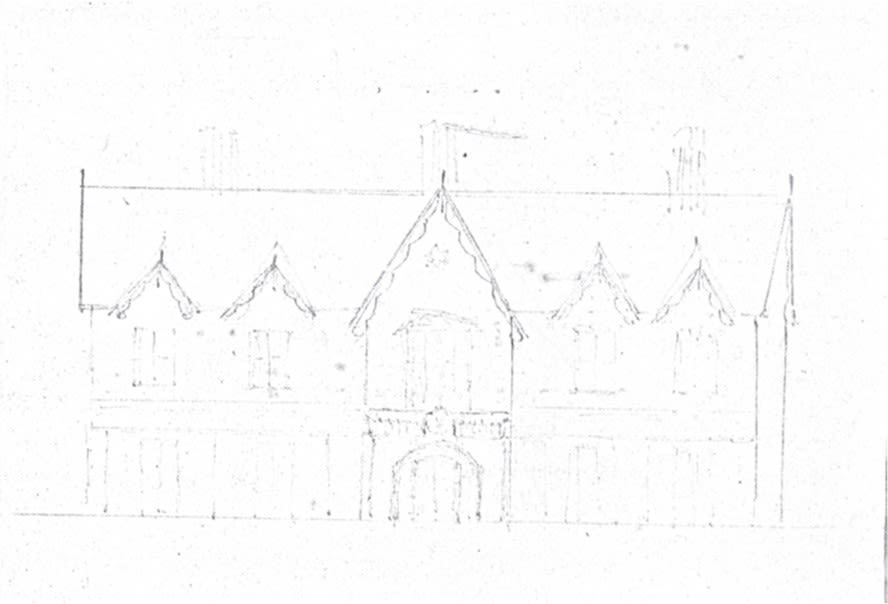

Details in pencil drawings in Marrianne's sketchbook can be seen on the two-storey building that was added behind the original Limestone Cottage.

Front elevation of house by Marrianne Campbell in her sketchbook c.1800s. National Library of Australia

Front elevation of house by Marrianne Campbell in her sketchbook c.1800s. National Library of Australia

'Limestone Cottage' was a single storey homestead built in the 1830s. The two-storey Duntroon house extension can be seen in the background of this photograph taken in the early 1870s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

'Limestone Cottage' was a single storey homestead built in the 1830s. The two-storey Duntroon house extension can be seen in the background of this photograph taken in the early 1870s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

It is likely Marrianne was supported by Alberto Soares when developing the final plans for Duntroon House. Soares was the clergyman at Christ Church in Queanbeyan, but also happened to be a talented architect, designing many of the states churches during this period.

Marrianne and Alberto had much in common: architecture, watercolour painting, the arts and religion. It is little wonder they made a connection. Coincidentally, they relocated to the district in the same year, 1857.

The new building included further bedrooms, nurseries, a breakfast room, morning room, servants' hall and cellar. For George, a study and library were added.

Brick and stone were used in the construction of this grand home. Research into the stonework and carved bargeboards indicated a prosperous family who wanted the most up-to-date styles, as well as skilled masons and builders in the area who could complete the project.

Aside from small tweaks to the building in 1876, Duntroon House has remained unchanged since this period.

One story written by a 'travelling correspondent' said of Duntroon house...

The residence at a distance has quite a palatial look, but on a nearer view the appearance is somewhat marred by the old house, which has been left in front and the fine new additions erected at the rear.

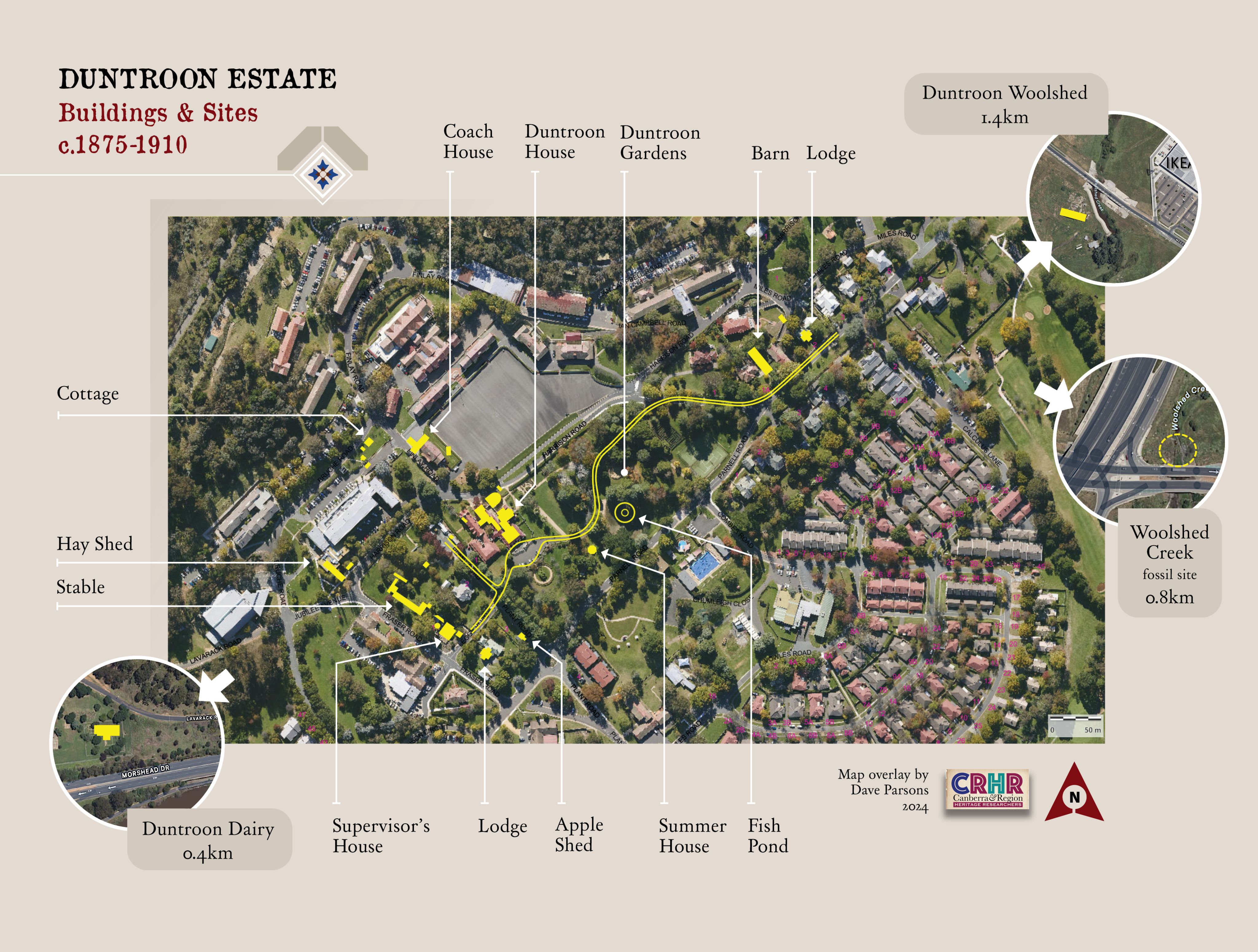

Duntroon Estate map showing key buildings and features, c.1875-1910. Overlay courtesy of Dave Parsons of Canberra & Region Heritage Researchers, 2024.

Duntroon Estate map showing key buildings and features, c.1875-1910. Overlay courtesy of Dave Parsons of Canberra & Region Heritage Researchers, 2024.

Duntroon Woolshed

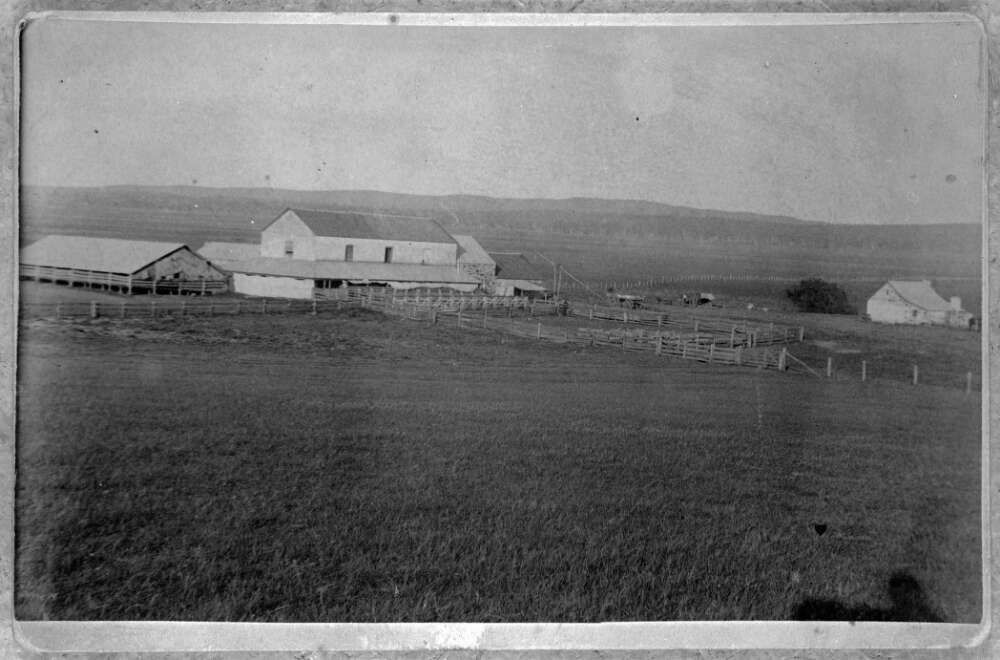

The Duntroon Woolshed was the first, the largest, and the best constructed woolshed from the early pioneering settlement period of the Limestone Plains.

ACT Heritage Register

Located near the Molonglo River, in the Majura Valley, within sight of the main Duntroon House and other key landmarks, the Duntroon Woolshed was a hive of industrious activity in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Campbell's began their sheep farm with 700 sheep brought by James Ainslie to the Duntroon/Pialligo site in the 1820s. In the following years, the Campbell family funded passages for shepherds, mostly from Scotland, to come to work on the expanding estate.

Keeping track of your livestock was essential. Owners would brand or tag their animals. The tags below bear the name 'Duntroon' and are numbered sequentially on the reverse.

Duntroon metal ear tags for sheep. Courtesy of the Australian Army Museum Duntroon.

Duntroon metal ear tags for sheep. Courtesy of the Australian Army Museum Duntroon.

A tag would be attached to each sheep's ear to identify those belonging to the Campbell family. This was important given the expansive estate prior to fencing as well as the identification of livestock as they came through the woolshed.

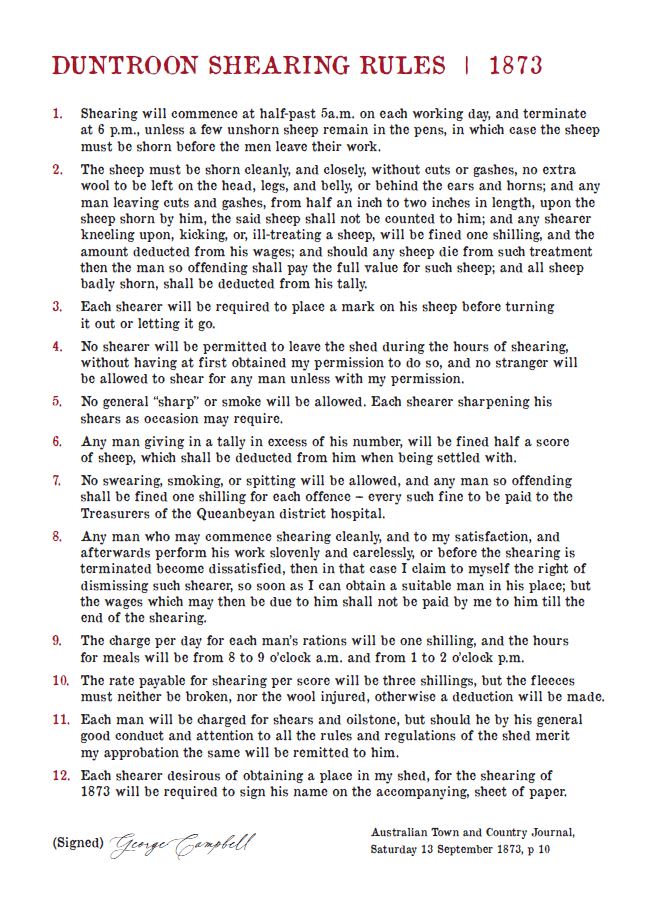

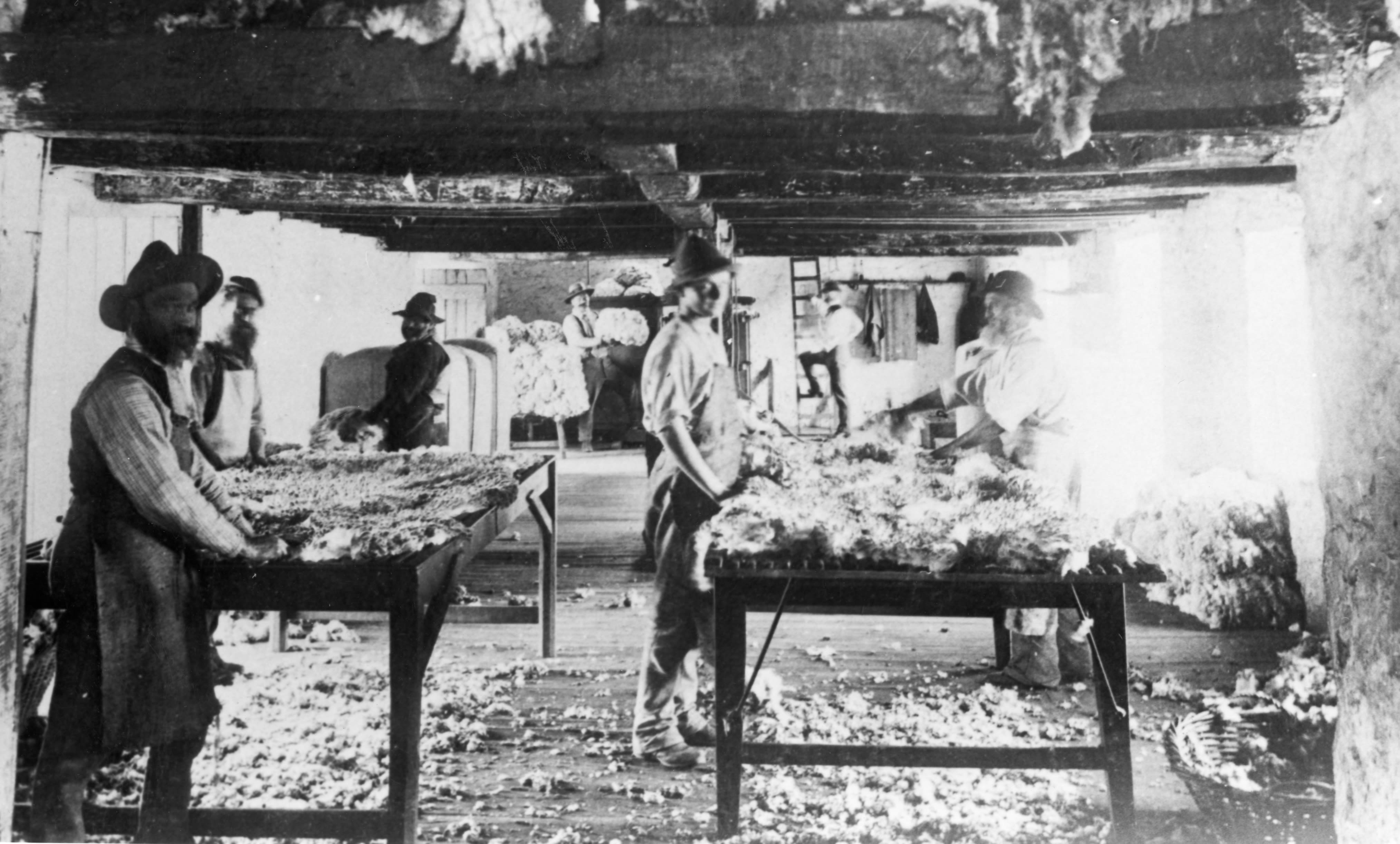

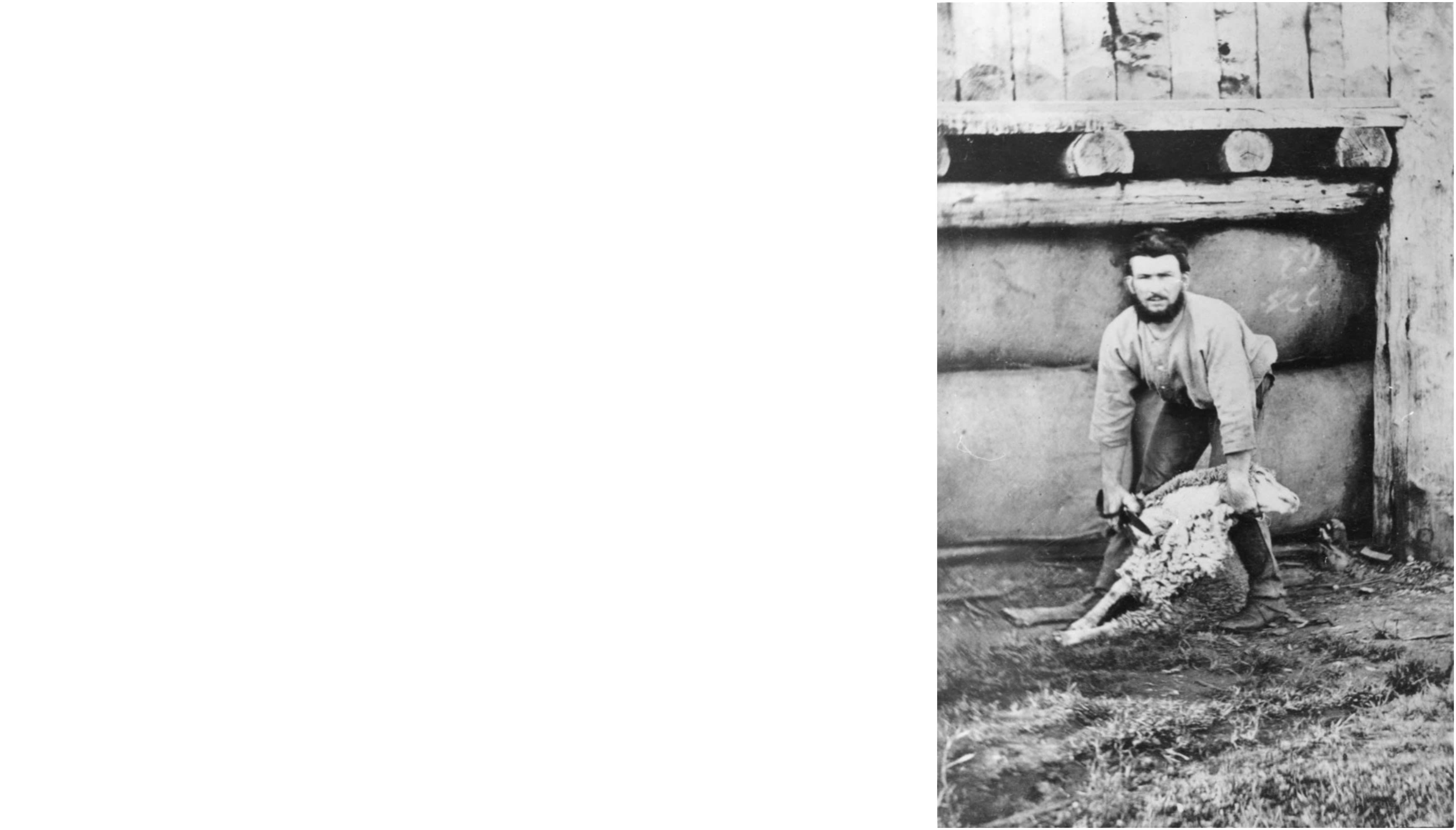

Shearing season would typically begin in October and run until November. Most shearers were independent labourers - they travelled the district, and further afield, during the season moving from one woolshed to the next.

Duntroon Woolshed was renowned for its strict rules - so much so that they were reported in the Australian Town and Country Journal.

In the 1870s, their work began at 5.30am and finished at 6pm. Labouring in the noisy, busy woolshed would only be broken by two one-hour breaks for meals during the long day. Although, there may have been singing in the shed as they worked.

Listen to the folk ballad, "The Bare Bellied Ewe". This song, from 1891, may have been sung by the shearers in the Duntroon Woolshed.

Shearers had no real rights (or representation) but the 1880s saw the establishment of unions for these independent labourers.

Once the sheep had been rounded up, the shearers would tackle the sheep into the shearing position. Stanley Howard, a visitor at the home of Reverend P.G. Smith of St John's Canberra, documented his first-hand experience of visiting woolsheds in the district in 1872...

At Duntroon they get through 1500 sheep in a day, often. Some of the shearers ‘nick’ the sheep dreadfully, which is not at all pleasant to see. A pot of tar and carbolic acid is kept at hand, and applied to these cuts. All the sheep were being shorn in the ‘grease’, so they did not look pretty and white as when they are washed: the fleece too weighs much heavier, being from five to seven lbs. Wool is high this year, and fetches, I believe, as much as 1/3d. in the ‘grease’. I saw the pressing apparatus, which is not used, I fancy in England, but is of course necessary out here on account of ship room. You can judge how tightly the bales are packed; for they are only about 5ft 6, by 9ft. and weigh from 550 to 800 lbs.

Hand shears were used to shear sheep in the 19th century, with sheepskin wound around the handles to allow for better grip. The blades of their instruments were kept sharp by using a grinding stone after shearing. Many, if not all shearers, came away with back injuries, puffy knuckles and swollen wrists.

Hand shears c.1800s. Courtesy of ACT Historic Places Collection

Hand shears c.1800s. Courtesy of ACT Historic Places Collection

Once the sheep had been shorn, the fleece was sent to the classing room where dedicated wool classers would group fleece based on length and thickness, quality, colour, strength and cleanliness. This ensured the Campbell's earned the highest value for their wool. There were dedicated roles in the shearing shed:

|

Terminology |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

'Boss' or 'Ringer' or 'Gun' |

Fastest shearer in the group |

|

'Carding' |

Untangling wool fibres |

|

'Classers' |

Sorts to shorn wool into type |

|

'Picker-ups' |

Sweep up the shorn wool |

|

'Tar boy' |

Waits with brush in hand to smear tar over cuts to stop bleeding |

|

'Wool presser' |

Wooden machine used to create bales of wool |

Wool classing room by Charles Kerry c. 1890. Courtesy of Canberra and District Historical Society.

Wool classing room by Charles Kerry c. 1890. Courtesy of Canberra and District Historical Society.

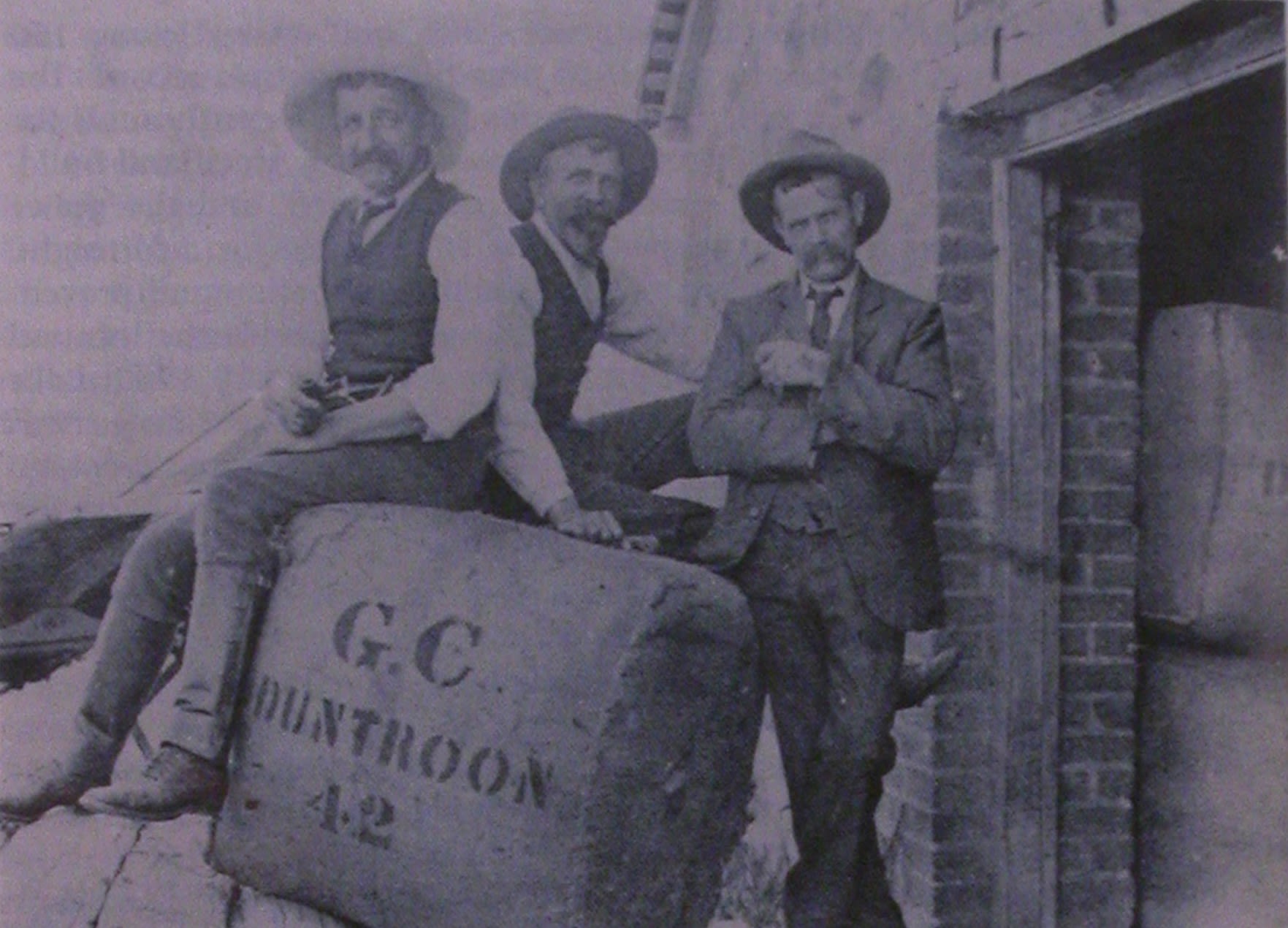

It would then be wrapped into huge bales and added to bullock drays (carts) to be transported across Australia, most likely to be loaded onto ships bound for Europe.

L-R: Ernest E. Hudson (Manager, Duntroon), William Mayo (Wool Classer) and Ernest Davis ('Boss of the Board'), c.1903 with packed wool 'G.C.' George Campbell, Duntroon. From "The Mayo Connection" by Wendy McLellan

L-R: Ernest E. Hudson (Manager, Duntroon), William Mayo (Wool Classer) and Ernest Davis ('Boss of the Board'), c.1903 with packed wool 'G.C.' George Campbell, Duntroon. From "The Mayo Connection" by Wendy McLellan

Annual Shearers Ball

After all the hard work, and the completion of each shearing season, the shearers, their families and other members from the community would celebrate the ‘cutting-out’ with a ball. It was held on the evening of the final shearing day at the Duntroon woolshed. The shearers had to hurry to prepare the shed for the ball that same evening. The shed was festooned with colour, as described in the local newspaper:

The bare walls were hidden with draperies and bunting; relieved with boughs of bright green. The tie-beams, rafters and roof were not only similarly decorated, but bright-coloured Chinese lanterns, and other lamps, illuminated the place.

The people from the district came from far and wide to celebrate this event. Music provided by local amateur musicians accompanied the dancing. A supper was held near midnight before the dancing recommenced. The balls would finish in the early hours of the following morning - a fitting celebration for the shearers and their community.

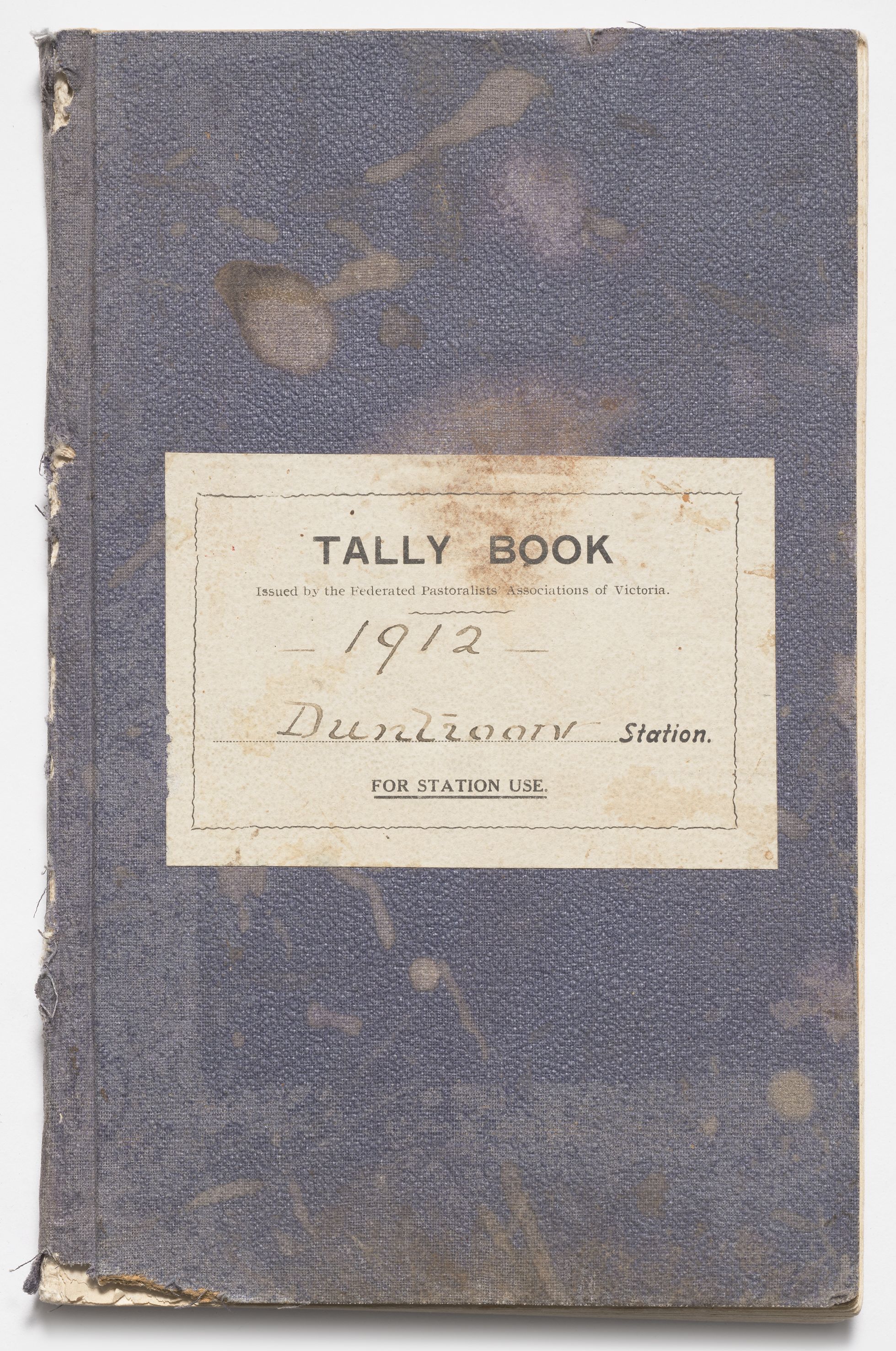

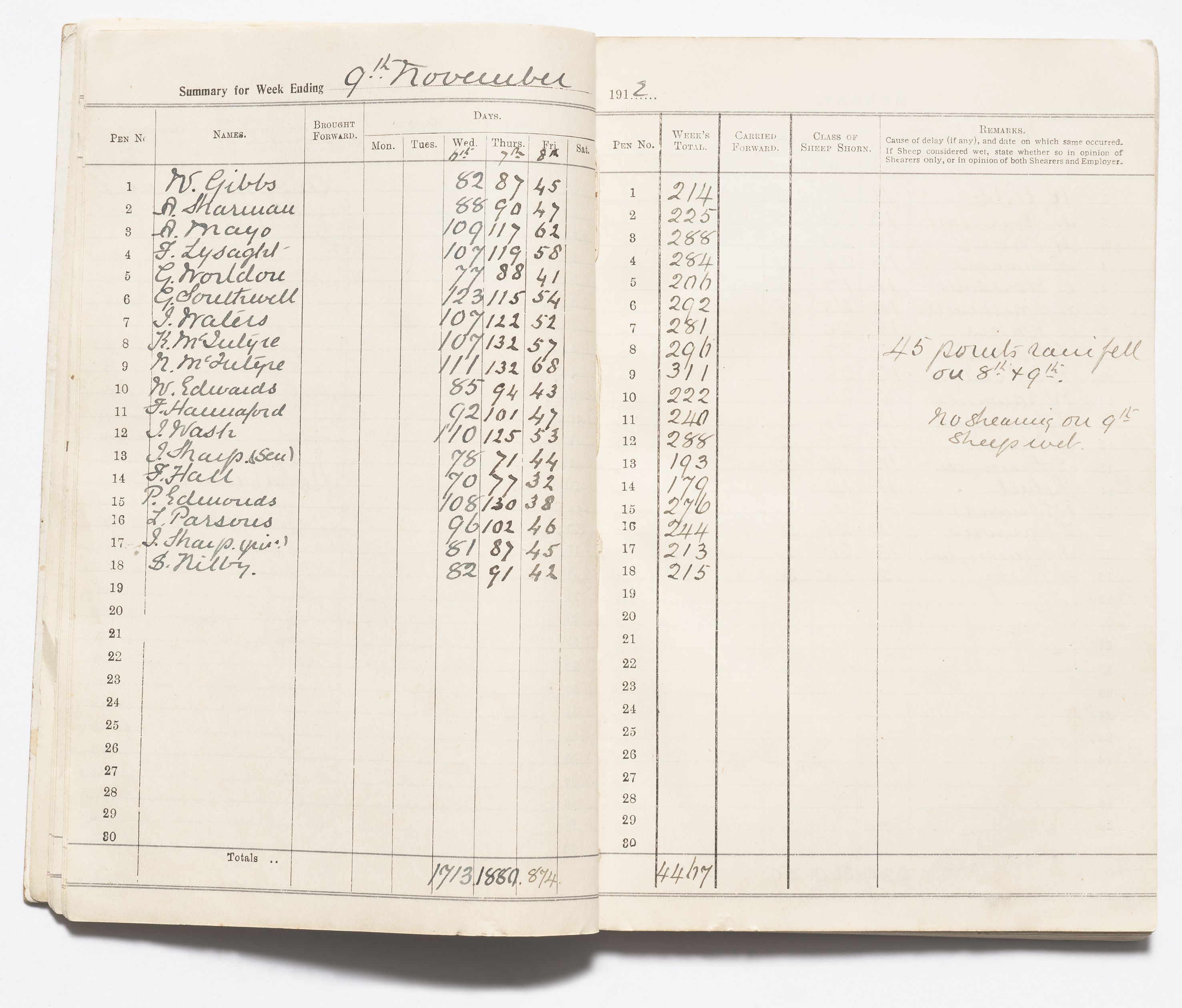

Keeping tally

This tally book recorded the achievements of the shearers employed at Duntroon Woolshed during the final shearing season of 1912. 'Points' of rain (equivalent to approximately 2mm of rain) are recorded as well as whether the sheep were wet and therefore could not be shorn. The number of sheep shorn was recorded daily and summed at the end of the week - the total equating to the amount of money each shearer would be paid (less any work deemed insufficient by the manager). At this stage, shearing had been mechanised and the shearers were using Wolseley shears.

Duntroon Woolshed Tally Book 1912. Courtesy of Canberra and District Historical Society.

Duntroon Woolshed Tally Book 1912. Courtesy of Canberra and District Historical Society.

Duntroon Woolshed Tally Book, 1912. On loan from the Canberra and District Historical Society

Duntroon Woolshed Tally Book, 1912. On loan from the Canberra and District Historical Society

Eighteen men were employed to shear that year from 6 to 25 November – between them, they sheared 20,809 sheep – some days were wet, so no shearing took place. They also sheared sheep for other families in the district, including the Darmody's and the Cameron's.

|

Shearer name |

Wed 6 Nov 1912 |

Thur 7 Nov 1912 |

Fri 8 Nov 1912 |

Total for week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

W. Gibbs |

82 |

87 |

45 |

214 |

|

A. Harman |

88 |

90 |

47 |

225 |

|

A. Mayo |

109 |

117 |

62 |

288 |

|

J. Lysaght |

107 |

119 |

58 |

284 |

|

G. Worldon |

77 |

88 |

41 |

206 |

|

G. Southwell |

123 |

115 |

54 |

292 |

|

J. Waters |

107 |

122 |

52 |

281 |

|

K. McIntyre |

107 |

132 |

57 |

291 |

|

N. McIntyre |

111 |

132 |

68 |

311 |

|

W. Edwards |

85 |

94 |

43 |

222 |

|

J. Hannaford |

92 |

101 |

47 |

240 |

|

J. Wash |

110 |

125 |

53 |

288 |

|

J. Sharp (Snr) |

78 |

71 |

44 |

193 |

|

J. Hall |

70 |

77 |

32 |

179 |

|

P. Edwards |

108 |

130 |

38 |

276 |

|

L. Parsons |

96 |

102 |

46 |

244 |

|

J. Sharp (Jnr) |

81 |

87 |

45 |

213 |

|

S. Kilby |

82 |

91 |

42 |

215 |

The Duntroon Woolshed still stands today. It is sandwiched between the Molonglo River and Pialligo shopping centre.

Did you know...

In 1844, William Branwhite Clarke, a friend of Robert Campbell, visited Limestone Cottage from Sydney. A geologist by training, Clarke headed to Woolshed Creek, presumably to examine the rocks. While there, he found the first Silurian sea creature (brachiopod) fossils in Australia. Clarke's finds were published in newspapers in Australia and internationally. His collecting practices, extensive research and knowledge, and scientific papers led to Clarke becoming known as the 'Father of Australian Geology'. Read more about Woolshed Creek fossils here.

Duntroon Dairy

Within a decade of Robert Campbell being granted the land at Duntroon/Pialligo, Duntroon estate had expanded, and buildings had been erected on the acreage. This dairy was built around 1832.

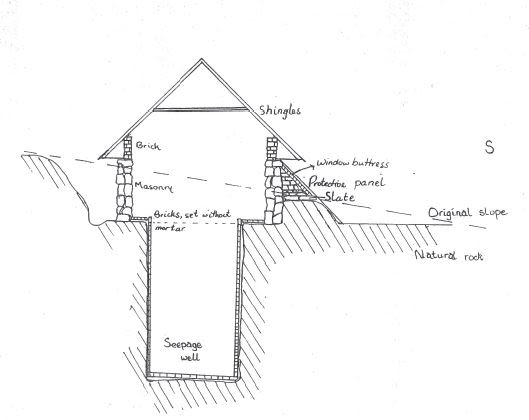

Although the first stock established at the estate were sheep, the sophisticated dairy design, including the drainage systems, suggest that cattle may have been the intended focus of the farming venture.

The dairy itself is a simple, but ingenious, design located in an ideal spot. Built on the southern slope of Mount Pleasant, it is sheltered from the rain and prevailing winds of the winter months and kept cool during the summer months. The view allows the dairymen and women to keep an eye on their cattle and the Molonglo River, which was prone to flooding. The dairy, which is reputed to be the oldest freestanding European building in the ACT, is 5m wide by 15m long.

A 'well' built under the dairy floor used drafts from the cool water running underground as an early form of refrigeration for the valuable dairy products produced on site.

A typical day at the dairy would have started at 4am – milking time. The rest of the day was spent making butter, cleaning, and tending to the cows, then milking again in the early evening.

As well as tending to the cows, there would have been a vegetable garden and other livestock, including chickens.

Many individuals and families have called the dairy home...

Isabella McPherson - recorded as the first dairywoman. She, husband Hugh, and family of four children at that time, voyaged to Australia via the ship, 'Asia' from Cromarty, Scotland. They were assisted migrants under Robert Campbell. In 1840, they headed to Duntroon Estate where Hugh became head shepherd based at Mugga-Mugga.

Brian Logue Junior, his wife and their children moved into the dairy. According to records, the dairy was viewed by visitors as a model of cleanliness and efficiency.

Local autobiographic writer and long-time resident Samuel Shumack told of his family relocating to Canberra in the 1850s. He recounted Duntroon dairy, the Logue family and their work:

When we arrived in Duntroon in 1856 Brian Logue and his family had charge of the dairy. He had six daughters and one son, and the dairy, which was a building 30 feet by 16 feet, was a model of cleanliness and efficiency. There were no separators in those days and milk was set in pans, sometimes as many as two dozen, from which the cream was skimmed each morning and placed in a vertical churn. I have seen the operators of these churns perspiring freely – there were no rotary churns then. An Autobiography, or Tales and Legends of Canberra

The Austen Family - In 1865, Ambrose and Grace Austen take over Duntroon dairy. Women were often involved in dairy farming – tending the dairy cows, milking them and producing the butter.

Although 1870-1873 were unproductive years, 1874 saw bumper crop yields meaning better fodder for cows and higher milk yields. It was at this time that dairies on the Limestone Plains were able to sell surplus produce for better prices. Goods were transported to expanding Sydney via bullock and cart (often taking six weeks to reach the buyer) with the risk of spoiling before reaching the final destination.

While there may have been difficult years for dairy produce, it seems the chickens at the dairy were unaffected...

Mrs Austin (sic), of the Dairy, at Duntroon, sent to the Queanbeyan Age office, a hen egg which measured 9½ by 8 inches, and weighed 8½ ounces. On being broken the prodigy was found to contain, besides the ordinary yolk and white, another full-sized egg, within a perfectly matured shell. The Queanbeyan Age, 2 October 1873

The Warwicks and Mayos - Alice Austen, daughter of Ambrose and Grace, married Frederick Warwick in 1881, and they took over the running of the Duntroon dairy from her parents.

Elizabeth Austen, another daughter of Ambrose and Grace married Joseph Mayo in 1874. Joseph was a shepherd for the Campbell family. The Mayo’s moved to Mugga Mugga cottage in 1880, from Stoneyhurst in Mugga Lane. Sadly, their time at Mugga Mugga was cut short by Joseph’s death in 1895, at which point the Campbell family moved Elizabeth and her five living children back to the dairy where she resided with her sister, Alice Warwick.

Daughters Alice Warwick and Elizabeth Mayo continued living there. Frederick Warwick was listed as the manager in 1908.

The Edlingtons - Elizabeth Mayo’s daughter Jennet and son-in-law Charles Edlington leased back land after the 1911 resumption where it was a sheep farm until the 1940s when government requested they revert back to dairy farming. In the early 1960s, the site was resumed again by the government; this time for the creation of Lake Burley Griffin.

A Dig at the Duntroon Dairy

In the mid-1970s, the dairy’s roof collapsed and the whole dairy site was in a state of neglect. Many of the buildings were deemed unsafe and demolished. Luckily, the dairy survived this fate, being recognised as a significant building in the ACT.

Dr Eleanor Crosby headed up the archaeological excavations in 1977, with the support of 40 local volunteers. It was the first archaeological dig to take place in the ACT. Across the four years spent at the site, upwards of 1,470 man hours were spent excavating and recording finds.

The work at the site also helped architects identify the materials used in the construction of the dairy and allowed for the building to be brought back to its former glory.

Some of the archaeological finds were transferred to CMAG in 2011. A number of fascinating objects that were found down the dairy well; three complete, ornate cast iron cots and three four-poster beds, farming implements, crockery and glassware. It appears the well was used as a tip for unwanted goods during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Duntroon dairy 'refrigerator' well. Courtesy of James Coleman

Duntroon dairy 'refrigerator' well. Courtesy of James Coleman

Side elevation of Duntroon Dairy showing seepage well and masonry with brickwork added by Ambrose Austen, Courtesy of Archaeological Work at the Duntroon Dairy ACT 1977-1981 Report by Dr. Eleanor Crosby.

Side elevation of Duntroon Dairy showing seepage well and masonry with brickwork added by Ambrose Austen, Courtesy of Archaeological Work at the Duntroon Dairy ACT 1977-1981 Report by Dr. Eleanor Crosby.

Duntroon Dairy double bed head excavated from Duntroon dairy well. Gift of ACT Property Group, 2011.

Duntroon Dairy double bed head excavated from Duntroon dairy well. Gift of ACT Property Group, 2011.

Other estate buildings & features

St John the Baptist Church

Early in the estate’s history, Robert Campbell offered two acres of land for St John’s Church to be built and contributed half of the costs towards its construction. The church, which was two miles from the Duntroon homestead, was built according to a sketch by Bishop Broughton and consecrated in 1845.

St John's Church, Canberra with unknown figure in foreground, c. 1862. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

St John's Church, Canberra with unknown figure in foreground, c. 1862. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

In the same year, alongside the church, Robert Campbell established a small schoolhouse for employees' and neighbours' children. The school was originally named Canberry School. The school had a contentious history due to the land it stood on as well as surviving a large fire in 1864 (children and teacher were moved temporarily to Duntroon dairy), removal of state subsidies and adequate accommodation for teaching staff. The school finally closed in 1913.

Honouring his father’s links with St John’s Church, George Campbell funded the design and building of a new spire for St John’s Church in 1868. The spire was designed by Edmund Blacket in the Victorian Academic Gothic style, typical of the era. At the request of George Campbell, Canon Alberto Soares designed a new nave and chancel as a memorial to Robert Campbell. Soares was the incumbent of Christ Church in Queanbeyan, and is often described as the first architect in the district.

The Parsonage

In the early 1870s, monies from the Campbell family and through public fundraising were raised to fund the two-storey brick St John’s Parsonage. Again, Campbell called on Canon Alberto Soares for the design of the new parsonage.

The new parsonage will be, in a few years, as nice a one of the kind as any in England; and the view from the drawing room window might bare comparison with more famous ones.

The parsonage was situated in the current Glebe Park and home to Rev. P.G. Smith from 1874 to his death in 1906. Reverend Smith was the Rector of St. John’s from 1855 until 1906 and during his time, planted elm, willow and poplar trees around the parsonage. Many descendants of these trees live on today in Glebe Park. The parsonage was renamed Glebe House in 1930 before it was demolished in the 1950s.

Duntroon Stables

Duntroon stables, c.1870. Possibly Frederick and Edward Campbell in front of stables. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Duntroon stables, c.1870. Possibly Frederick and Edward Campbell in front of stables. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

This rather grand building would have housed the prized horses of the Campbell family. While the district’s economic strength lay in wool, supplemented on some properties by wheat, the Campbell's had a special interest in horse breeding.

[George Campbell] is very wealthy; drives well-bred and well-kept horses, and generally has a coachman in livery, which is a rare sight so far away from Sydney

Livery buttons used by the Campbell family coachman, c. 1893. On loan from Margot Shannon (nee Campbell)

Livery buttons used by the Campbell family coachman, c. 1893. On loan from Margot Shannon (nee Campbell)

The Campbell’s overseer, Allan McLachlan, brought prize-winning stallions to Duntroon for breeding. The high-quality horses on the estate were noted during a journalist’s visit to Duntroon in 1877. He reported:

Close to the super’s residence are a range of stables and loose boxes… a large number of mares are roaming over the run, from which some capital coaching horses and roadsters are bred.

Ariel and Akbar, George Campbell's horses, at the back of Duntroon House. c.1880s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Ariel and Akbar, George Campbell's horses, at the back of Duntroon House. c.1880s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

The conservatory

Rear aspect of Duntroon House showing conservatory in centre, greenhouse to its left, and summer house with conical roof on far left, c. 1870s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Rear aspect of Duntroon House showing conservatory in centre, greenhouse to its left, and summer house with conical roof on far left, c. 1870s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

The original, simple pitched-roof greenhouse, which was built around 1862, was replaced in the mid-late 1870s by a multi-sided conservatory and separate potting shed.

Inside the conservatory, there was a rockery with pieces of quartz (likely from the Campbell's nearby mine), stalactites and stalagmites, and shells that were accentuated with ferns and a fountain.

In the centre of the conservatory was a brick-cemented pyramid with tiers of potted plants of many varieties. The pyramid was framed by a lemon and orange tree; one on each side.

Mr Lewis, the head gardener, propagated and grew native and exotic flora, including cactus and orchids.

The Aviary

Located near the original conservatory (greenhouse), the aviary housed many native and exotic birds, including green leek (superb parrot) and lowry (crimson rosella) paroquets, diamond sparrows (diamond fire-tail finches), and a golden pheasant from China.

Diamond Fire-tail Finch (2) Zonaeginthus bellus, in Volumes 5-6: Birds of Australia collection, [1887-1891] by Gracius Joseph Broinowski. Courtesy of the State Library of NSW.

Diamond Fire-tail Finch (2) Zonaeginthus bellus, in Volumes 5-6: Birds of Australia collection, [1887-1891] by Gracius Joseph Broinowski. Courtesy of the State Library of NSW.

Apple Shed or Bee House?

"Apple Shed", or building C58, Duntroon Estate. Courtesy of Hannah Paddon

"Apple Shed", or building C58, Duntroon Estate. Courtesy of Hannah Paddon

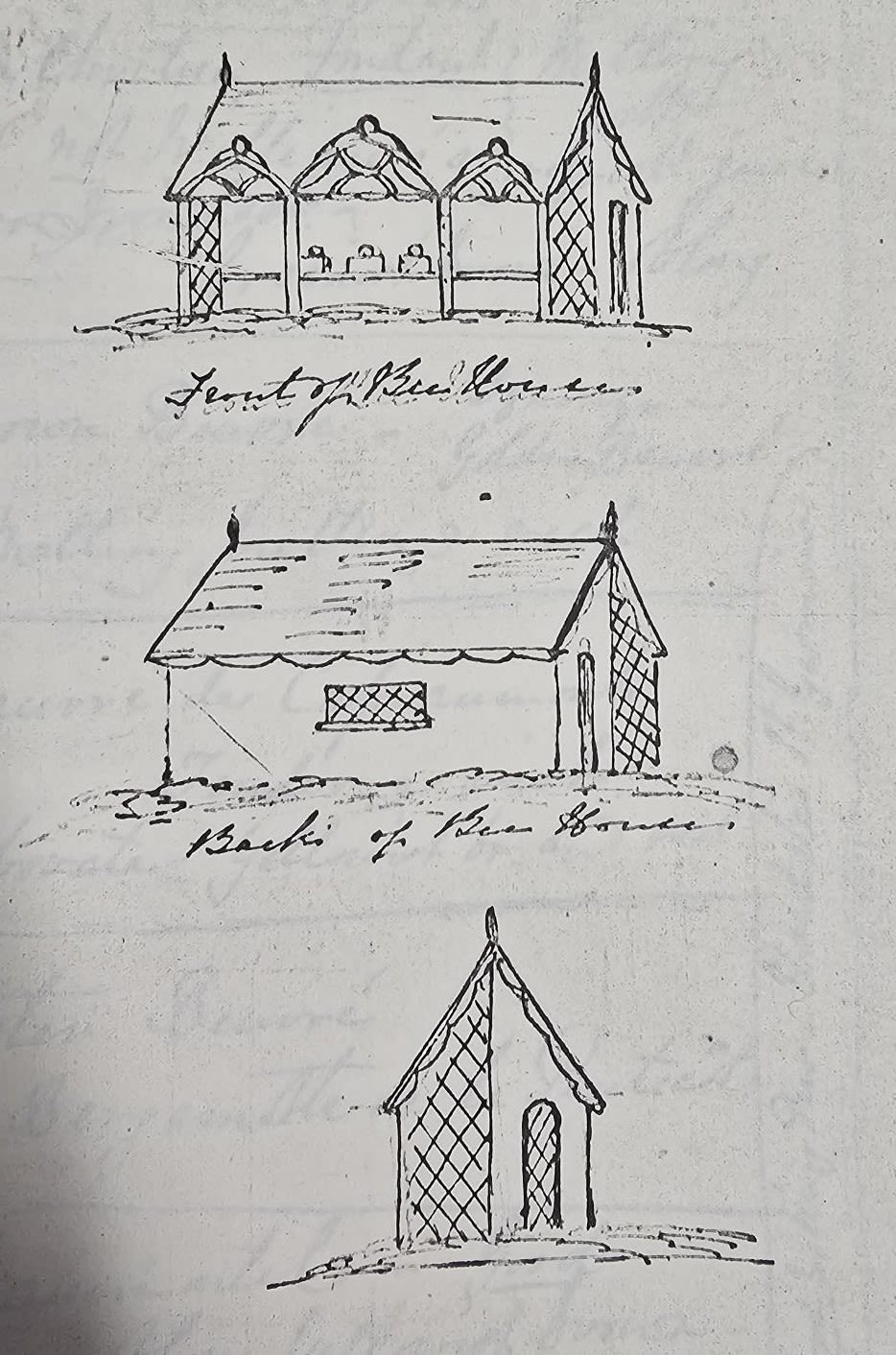

The Apple Shed is believed to have been converted from its original purpose as a bee house. A sketch in Marrianne Campbell's notebook looks very similar to the once open-sided shed. The decorative bargeboards are similar to those on the 1862 two-storey Duntroon House extension. The lattice woodwork in the drawing is also similar to woodwork added to cottages on the estate.

Bee house sketch from Marrianne Campbell's notebook. Courtesy of the RMC Duntroon Australian Army Museum

Bee house sketch from Marrianne Campbell's notebook. Courtesy of the RMC Duntroon Australian Army Museum

Duntroon Windmill

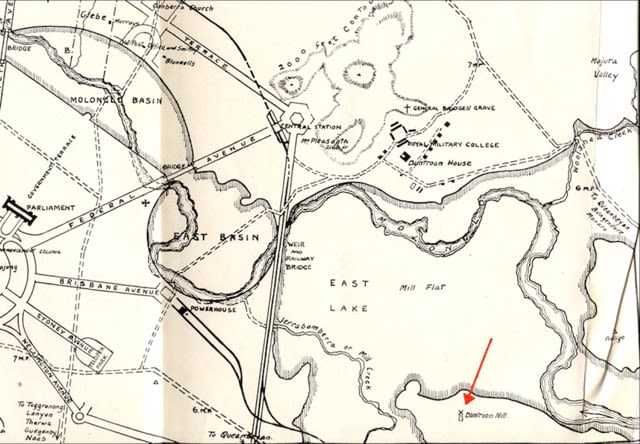

Did you know, Duntroon estate once had a windmill? The windmill was located on a shallow hill to the southeast of the house.

Map taken from Canberra’s Last One Hundred Years, 1924. By Frederick W. Robinson

Map taken from Canberra’s Last One Hundred Years, 1924. By Frederick W. Robinson

It was built in the early 1860s and operated by the Gregory family. Head of the family, John Gregory, and his sons worked, often during the night to take advantage of the wind, to mill flour for the whole district.

The windmill stood for at least a decade before being uprooted and ruined during a massive storm on Saturday 21 November 1874.

So complete was the destruction that the machinery is said to be hopelessly damaged, and the mill-stones themselves reduced to small fragments.

The cottages

Gardeners Cottage, Duntroon estate. c.1870s-1880s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Gardeners Cottage, Duntroon estate. c.1870s-1880s. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

There were many workers cottages across the Duntroon estate, including the gatehouse lodges for the overseer. The image of the gardeners cottage shows the ornate bargeboards and lattice work detail.

The head gardener in the 1860s and 1870s was Frederick Lewis. A report in the local Queanbeyan newspaper records Frederick's skill in growing "Monster" vegetables:

Mr Lewis, head gardener to G. Campbell, Esq., having in the garden at the present time, a cucumber measuring 27 1/2 inches long by 11 1/2 inches in circumference.

The gardeners cottage is likely Waller or Shappere Cottage (as now known). They were extended by the Royal Military College for staff use in 1913.

End of an Era

In 1913, the Duntroon estate was sold off following the government’s resumption of the land and buildings for the establishment of RMC Duntroon within the Federal Capital Territory (to become the Australian Capital Territory).

A massive stock and house sale occurred on 11 and 12 July 1913. Ewes and rams were the first to be sold on Friday morning, the Duntroon shearing shed was also submitted for sale on the Friday, and after lunch that day horses and cattle would be sold. Saturday saw the sale of house effects and those of the manager, E. E. Hudson.

Descendants of many of the families that lived and worked on Duntroon estate, including members of the Campbell family, still reside in the district.

Family group at Duntroon. Sophia Campbell (far left) and Marrianne Campbell (far right). c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Family group at Duntroon. Sophia Campbell (far left) and Marrianne Campbell (far right). c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Goat buggy with Campbell children (possibly Frederick and Edward Campbell with white shirts) outside Duntroon stables. c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Goat buggy with Campbell children (possibly Frederick and Edward Campbell with white shirts) outside Duntroon stables. c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Duntroon House driveway - four unidentified people; far left likely gardener (possibly Frederick Lewis), c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Duntroon House driveway - four unidentified people; far left likely gardener (possibly Frederick Lewis), c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Frederick, Edward and Sophia Campbell in the Duntroon House gardens, overlooking the Molonglo River and further south, c.1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Frederick, Edward and Sophia Campbell in the Duntroon House gardens, overlooking the Molonglo River and further south, c.1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Goodmans Cottage (likely Duntroon estate) with unknown female, c.1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Goodmans Cottage (likely Duntroon estate) with unknown female, c.1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Frederick Mayo (left) and Joseph Mayo (right) - brothers who lived and worked on Duntroon estate, c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Frederick Mayo (left) and Joseph Mayo (right) - brothers who lived and worked on Duntroon estate, c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Sarah Campbell (left) and Sophia Campbell (right) on the verandah of 'old' Duntroon House (Limestone Cottage), c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Sarah Campbell (left) and Sophia Campbell (right) on the verandah of 'old' Duntroon House (Limestone Cottage), c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Goodman Cottage, likely designed by Marrianne Campbell, with unknown male gardening, c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Goodman Cottage, likely designed by Marrianne Campbell, with unknown male gardening, c. 1870s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Susan and George Campbell, c. 1900s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Susan and George Campbell, c. 1900s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Cottage on Duntroon estate which was located near the stables (since been demolished), possibly Mrs Landers and son in photograph, c. 1870-90s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Cottage on Duntroon estate which was located near the stables (since been demolished), possibly Mrs Landers and son in photograph, c. 1870-90s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

(L-R): John McPherson (shepherd and horse breaker), Frederick Lewis (head gardener), Sarah Campbell, Marrianne Campbell, Sophie Campbell, Fraulein Dittenburger, Frederick Campbell, Edward Campbell, Allan McLachlan (overseer) c. 1872 on the lawn of Duntroon house. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

(L-R): John McPherson (shepherd and horse breaker), Frederick Lewis (head gardener), Sarah Campbell, Marrianne Campbell, Sophie Campbell, Fraulein Dittenburger, Frederick Campbell, Edward Campbell, Allan McLachlan (overseer) c. 1872 on the lawn of Duntroon house. Courtesy of Robert Campbell

Acknowledgements

This exhibition would not have been possible without the support, loans, knowledge sharing and enthusiasm of:

The Campbell Family, particularly Robert, Margot, Pat and Emma

The Australian Army Museum Duntroon, with special thanks to Steve Medforth and Vanessa Roth

Canberra and District Historical Society, with special thanks to Nick Swain

The Edlington Family, particularly Jane and Cathie

Linda Roberts, Tony Maple, James Coleman and Celia Cramer

Contact us

Did your ancestors have a connection to the early Duntroon estate? Do you have photographs of some the people mentioned in the exhibition? Do you know of objects that relate to the district in this period that are held in private collections? Maybe you have some tales from your ancestors that are keen to share...

If so, the CMAG team would love to hear from you. Please send an email to our curators at cmag@act.gov.au and someone will be in touch.